Early History of Playing Cards & Timeline

Out of an apparent void, a constellation of references in early literature emerge pointing to the sudden arrival of playing cards, principally in Belgium, Germany, Spain and Italy around 1370-1380. Discover the early history of playing cards in our timeline from 50AD to the 15th century.

Playing Cards are believed to have originated in China and then spread to India and Persia. From Persia they are believed to have spread to Egypt during the era of the Mamluk Sultinate, and from there into Europe through both the Italian and Iberian peninsulas in the second half of the 14th century.

The game of playing cards was in vogue in West European countries by around 1375...

The history of playing cards in Western civilisation commences around 1370-1380. Out of an apparent void, a cluster of references in early literature (inventories of possessions, edicts, city chronicles and account books) emerges pointing to the sudden arrival of playing cards, principally in Belgium, Germany, Spain and Italy and very soon afterwards we hear of them being banned or controlled by the authorities.

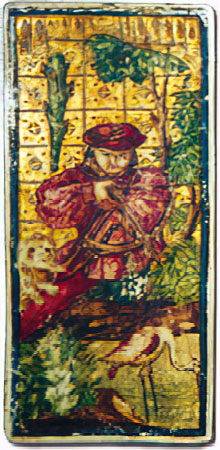

As well as the literary evidence, we can also look at contemporary illustrations of card playing. Dice and certain board games were already long-established; playing cards were a new addition to the repertoire of gaming pastimes. Unlike their Islamic predecessors, in which depictions of the human image were forbibben for religious reasons, Western playing cards carried images of real people on the court cards. The emotional response to the these colourful images, the suit symbols, players' perceptions of the imagery of the pack, patterns of logic, thought and other areas of behaviour all contributed to the rapid rise of a new and inter-related economy of playing card manufacture and consumption, employment opportunites, forms of entertainment, political and legal reactions etc as playing cards were assimilated into Western culture.

They also were a contributing factor to anti-social behaviour on account of the dishonesty or cheating which occurred in the less-reputable gaming houses. This led inevitably to bans and prohibitions as preachers demonised the game and the authorities devised ways to regulate the new craze. At the same time, we learn that upper classes and nobility enjoyed courtly games and also spent sums of money at gambling with impunity see ‘Playing Cards and Gaming’ →

Above: card playing and gambling was a magnet for anti-social behaviour on account of the dishonest characters, card-sharps, pimps and braggarts who were drawn to the less-reputable gaming houses, ready to fleece the unwitting visitor. A whole underclass of confidence tricksters and professional swindlers were attracted to the gambling dens, yet at the same time card playing was enjoyed as a leisurely and agreeable pastime amongst the upper class gentlemen and nobility.

How it all began

-

50 A.D. CHINA

Silk and tea, porcelain, paper, playing cards, and probably gunpowder were among China’s gifts to the West. Other examples are found in the study of such games as dice, chess, and backgammon, whilst the spread of playing cards was closely related to printing.

According to Chinese chronology, the art of printing was discovered in China at this period, under the reign of Ming Tsong the First, the second emperor of the Tartarian dynasty.

Paper has everywhere been the forerunner of printing.

-

105 A.D. CHINESE INVENTION OF PAPER

---1023.jpg)

Above: a Jiaozi, introduced in 1023, redeemable for 770 mò. These notes were printed from hand-carved wooden blocks or copper plates. The first paper money was a development of the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). [3]

The Chinese official record formally dates the invention of paper, one of the most monumental of Chinese inventions, as A.D. 105, but the invention was actually a gradual process perfected over some time.

The following account of the invention, as written by Fan Yeh in the fifth century in the official history of the Han dynasty, among the biographies of famous eunuchs, is taken from Carter (1931), p.5:

“In ancient times writing was generally on bamboo or on pieces of silk, which were then called 'chih'. But silk being expensive and bamboo heavy, these two materials were not convenient. Then Ts’ai Lun thought of using tree bark, hemp, rags, and fish nets. In the first year of the Yiian-hsing period (AD 105) he made a report to the emperor on the process of papermaking, and received high praise for his ability. From this time paper has been in use everywhere and is called the “paper of Marquis Ts’ai.”

The secrets of the manufacture of paper were subsequently passed on by Chinese prisoners to their Arab captors at Samarkand in the eighth century. Later on Moorish subjects passed their knowledge to their Spanish conquerors in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. This is basically the same paper which we use today. See How Paper is Made ►

The Chinese inventions of paper and printing were to be key factors in the reawakening of Europe when the time came over 1,000 years later.

-

6 or 7 C. EGYPT

Earliest examples surviving of textiles printed with wood blocks in Egypt.

-

c.750-800 CHINA

Early Description

Above: old Chinese playing card,, found near Turfan, date uncertain but probably c.1400. 9.5 x 3.5 cm.

The Kuei T'ien Lu, a book of anecdotes written in the eleventh century by the historian Ou-yang Hsiu, has been cited as placing the invention of playing cards in the middle of the T'ang dynasty (618-906), that is to say, about the time when the earliest books were printed in the 9th. century. However, in early references such as this one, the Chinese word for playing cards (yeh tzu) apparently implied dominoes or domino cards, which are early ancestors of what we think of today as playing cards.

More generally speaking, Carter (1931, p183) writes "cards belong to the group of games that had spread over a considerable part of Asia before the Crusades." He further writes "there is little doubt that both playing cards and dominoes originated in China and that both games were influenced by certain forms of divination and the drawing of lots and possibly by paper money. There are certain indications that the development of playing cards took place at about the same time as the transition from manuscript rolls to paged books. As the advent of printing made it more convenient to produce and use books in the form of pages, so was it easier to produce cards. These “sheet-dice,” as they were called, began to appear according to Ou-yang Hsiu (1007-72) before the end of the T’ang dynasty, and, if this is true, they were one of the earliest forms of block printing in China, as they were later in the West".

"With the Sung dynasty (960-1280) it seems probable that the evolution of these “sheet-dice” took two forms. Some continued to be printed on cards, and these grew more complicated, developing various picture forms and conventional designs—the ancestors of both Chinese and European playing cards. Others came to be made on bone or ivory, and as these were more difficult to produce, they remained for some time relatively simple (dominoes), but later these also developed more complicated forms, one of which has come to the Western world under the name of mah-jongg." Carter (1931, p184)

China had been issuing paper money for more than a century when Christendom saw its first paper. China had been on a paper money basis for four hundred years when block printing began in Europe. Chinese paper money was still being issued during Gutenberg’s lifetime.

-

764-770 JAPAN

First authenticated prints rubbed from wood blocks (text) are Buddhist charms printed in Japan.

-

868 CHINA

Earliest picture printed from a wood block is in a roll of the Diamond Sutra by Wang Chieh, but which must have had predecessors. Examples of colour printing from woodblocks also date from about the same period. By the tenth century AD printing on paper was widely available in Dunhuang and was popular as a cheaper way of producing images. As in Europe six centuries later, the earliest use of printing in China was fuelled by the desire to spread religious texts and images.

-

950 IMPORTATION OF ORIENTAL PAPER INTO SPAIN

For its first six hundred years papermaking was a Chinese monopoly, until taught to the conquering Arabs by Chinese prisoners at Samarkand, on the Silk Road, the ancient trade route linking China to the Mediterranean.

For the next five hundred years papermaking in the West was an Arab monopoly until the Arabs in turn taught their Christian conquerors in Spain. It was in 1150 that El-Edrisi said of the city of Xativa “Paper is there manufactured, such as cannot be found anywhere in the civilized world.” However, Spanish paper manufacture was still in Saracen hands and for another century Europe’s paper was largely supplied by the Saracen mills of Damascus and Spain.

A mill was established in France before the end of the XII c., and Italy, which founded its earliest factory at Fabriano about 1276, remained the most important source of supply in Europe throughout the XIV c. Manufacture was introduced into Germany in the last decade of the XIV c., in England at the end of the XV c., but in the Netherlands apparently not before the XVI c. During the XV c. Germany as well as France gradually became self-supporting in paper; South Austria would turn more to Italy for supplies; England to France and Italy by sea, and the Netherlands chiefly from France and Germany. It seems unlikely that any large supplies of paper were available before the latter part of the XIV c., and this was probably an important factor in determining the period at which the printing of pictures was introduced.

-

969 CHINA

The earliest certain date for Chinese playing cards is an entry in the 'Liao shih' of T'o-t'o, a history of the Liao dynasty (907-1125) written in the 14th. C. saying that Emperor Mu-tsung played cards on the night of New Year's eve.

-

1041-49 CHINA

First record of the use of moveable type, made from earthenware or tin, but which were never largely used.

-

Twelfth century references to playing cards.

A twelfth century treatise on the Game of Chess by Jewish Rabbis contains references to playing cards. This is a translation from Hebrew by Léon Hollænderski of “Délices Royales ou Le Jeu Des Échecs, son histoire, ses règles et sa valeur morale par Abraham ibn Esra (1089?-1164) et Aben-Yé’hia, Rabbins du XIIe siècle” published in Paris, 1864.

![Délices royales, ou le Jeu des échecs : son histoire, ses règles et sa valeur morale / par Aben-Ezra [Abraham ibn Esra] et Aben-Yé'hia [Bon-Senior ibn Iaḥia], rabbins du XIIe siècle ; traduction de l'hébreu par Léon Hollænderski, 1864. Source gallica.bnf.fr Délices royales, ou le Jeu des échecs : son histoire, ses règles et sa valeur morale / par Aben-Ezra [Abraham ibn Esra] et Aben-Yé'hia [Bon-Senior ibn Iaḥia], rabbins du XIIe siècle ; traduction de l'hébreu par Léon Hollænderski, 1864. Source gallica.bnf.fr](images/subjects/history/hebrew-chess-reference.jpg)

Above: a reference to playing cards in a 19th century translation of a 12th century Hebrew treatise on the Game of Chess. Bibliothèque nationale de France • Délices royales, ou le Jeu des échecs : son histoire, ses règles et sa valeur morale►

There are four references to playing cards, the first is on p.29: « L'aîné, pour corriger son frère cadet, qui était enclin au jeu des cartes, se disputa avec lui, lui fit de la morale, et parfois le gronda et le frappa, sans que cela pût le faire changer » ("The elder brother, in order to correct his younger brother, who was inclined to play cards, argued with him, lectured him on morality, and sometimes scolded and struck him, yet none of this could make him change.") Three further similar references occur on pages 31, 36 & 41. Source gallica.bnf.fr

-

1300 CHINA

Use of moveable wooden type.

-

JAPAN

Outside the Mongol Empire there was an issue of paper currency in Japan between 1319 and 1327.

Arrival of Playing Cards into Europe

Above: item described as “Fragmentary Playing Card, ink and colors on paper, 8 x 4 1/4 in. (20.32 x 10.79 cm), Egypt, 13th-14th century”. Los Angeles County Museum of Art M.2002.1.650►

We are doubtful this is actually a playing card, on account of the size, etc. See a better example under c.1400 EGYPT (below).

Although a number of early books describing the history of playing cards report the existence of manuscripts which mention playing cards (naibi) as early as the end of the thirteenth century, these cannot be verified and are disregarded. It is of course possible that rumours or accounts of cards had arrived from foreign lands via travellers, soldiers, captives, merchants or Arabic literary sources. Helen Farley (2009) mentions several of these in note 13, page 178.

Apart from the single example of Mamluk cards, there are several early references to 'moorish'-type cards in Barcelona during late 14th and early 15th centuries. During that period Spain was of course occupied by the Moors until 1492. Arabic literature was published there, and cards apparently also used there. Before cards arrived in Europe, there may have been some earlier continuity of their existence in Islamic territories, even though they were officially banned. For example, Ibn ’Abdūn in his Tratado de Hispa (a sort of good behaviour guide, Seville, early 12th century) wrote that sinful games of chance should be disallowed as they distract from religious duties and mindfulness of God, when in fact many games and sports were popular and privately enjoyed whilst religious injunctions were disregarded. Many of these games had been introduced into the Iberian peninsula by the Arabs. Ibn ’Abdūn, a devout Muslim of the Almoravid dynasty, merely places these games on the same level as consumption of alcohol, which was banned by Mohammed in the Koran, in order to preserve law and order. Hence few early references to games have come down in Andalusian records, and none to cards.

-

1347 BUBONIC PLAGUE

The ‘Black Death’ first touched the West, and within a few years perhaps a third of the population of Europe perished in the epidemic of 1347-50. The plague was a disaster for European trade and ruined those industries which needed a large labour force such as agriculture, mining and fisheries. Playing cards do not appear to have existed in Europe at this time. Important 14th century writers such as Petrarch, Geoffrey Chaucer and Boccaccio never mentioned playing cards in their writing.

-

1364 St. GALLEN, SWITZERLAND

Gambling(Switzerland) An ordinance forbade dice games, allowed board games, but left cards unmentioned.

-

1371 CATALONIA, SPAIN

The word naip appears in the Llibre de Concordances, a Catalan rhyme dictionary compiled by the poet Jaume March in 1371, which had been commissioned by the King of Aragon, Pere IV. The Catalan word ‘naip’, which has no other meaning apart from ‘playing card’, appears on page 63, line 1299, suggesting that playing cards were already known at that time, in popular usage. This pushes the date of their possible introduction to the late 1360s. The dictionary has been re-published in 1921 by Antoni Griera and is also available online: Diccionari de rims►

Above: excerpt from page 63 in Llibre de Concordances by Jaume March (1371) re-published by Antoni Griera, Institut d'estudis Catalans, Barcelona, 1921. Line 1299 contains words rhyming with -ip.

Prohibition The first references to the prohibition and subsequent regulation of card games.

The dilemma was that although the game was invented as a recreation and sociable pastime, if abused it led to idleness, uncivil behaviour or violent arguments in the lower strata of society. Therefore card games needed to be regulated and controlled. The regulation of games began in Roman law, but it is in medieval legislation where we find that specifically games of chance (and gambling) were often forbidden. However, in spite of this, playing cards continued to flourish in daily life amongst the local population. This continual and habitual transgression undoubtedly was tolerated by local authorities. In other words, the law was applied arbitrarily, depending on the circumstances of the moment, the relationships between officers of justice and the card players, etc. Fines might be levied and bribery or corruption also played a part. This went on and over time stricter ordinances and laws were enacted against games of chance, and monopolies and licences were brought in to derive revenues from gambling and the playing card industries.

-

1376 FLORENCE, ITALY

Prohibition23 May. A game called ‘naibbe’ is forbidden in a decree, with the implication that the game had only recently been introduced there.

NOTE: In the above two references, the word naip or naibbe is used for playing cards. This appears to derive from the Arabic na’ib (deputy, viceroy, governor) who is a court figure in the Mamluk cards. However, the Arabic word for playing cards is kanjifah, which is related to the Persian ganjiveh and Indian ganjifa. This supports the belief that whilst playing cards originated in China, they then spread to India and Persia. From Persia they are believed to have spread to Egypt during the Mamluk era, and from there into Europe through both the Italian and Iberian peninsulas in the second half of the 14th century.

-

1377 BASLE, SWITZERLAND

Early Description

Above: “Tractatus de moribus et disciplina humane conversationis” wirrten by Brother John, a Dominican friar and writer who published the oldest known description of playing cards in Europe. [1]

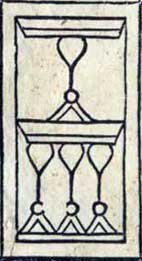

“Tractatus de moribus et disciplina humane conversationis” written by a Dominican friar by the name of John.

The pack described by him “in its common form, and that in which it first reached us”, comprised four seated kings, on royal thrones, each one holding a certain sign in his hand, of which signs some are reputed good, but others signify evil. Under which kings are two ‘marschalli’, the first of whom holds the sign upwards in his hand, in the same manner as the king; but the other holds it downwards in his hand. After this there are ten other cards, outwardly of the same size and shape, containing pips one to ten, making a total of 52. This description corresponds not only to our modern poker pack, also to many German packs, but also to the Egyptian Mamluk pack which has a “First” and “Second” viceroy (Na’ib). Brother John forgot to describe the suit signs, however.

He goes on to describe variant packs containing queens, or two kings and two queens each with their ‘marschalli’, or packs containing five or six kings each (i.e. 5 or 6 suits) with ‘marschalli’, or even four kings, four queens and so on making packs of up to 60. It may come as a surprise that so many innovative ‘variant’ packs existed so soon after the introduction of playing cards. The craze for new games was quite unbridled. We can see packs fitting these descriptions from fifty to a hundred years later (Stuttgart pack, Ambras Hofjagdspiel, Liechestein pack, Master of the Playing cards, de Dale, etc.), but how can they be explained so soon?

Note: Michael Dummett (1980) discusses Brother John's sermon, suggesting that the text may have been updated by a scribe at a later date, when more variants had emerged. He also says that it would be strange for Brother John to have written, "the form in which they first reached us", if, in the course of that same year, he had encountered five other forms.

-

1377 PARIS, FRANCE

ProhibitionOrdinance forbade card games on workdays.

-

1377 SIENA, ITALY

Reference to playing cards.

-

1378 REGENSBERG, GERMANY

Reference to playing cards.

-

1378 ITALY

The Proviggione refers to a 'ludus qui vocavit naibbe' ('a game called cards').

-

1379 St GALLE, SWITZERLAND

ProhibitionCard games prohibited.

-

1379 VITERBO, ITALY

Early Description

The year in which it is claimed that a new game called 'nayb' was introduced by a 'Saracen' (Oriental, Arab or Muslim). In other words, Arabic or Saracenic playing cards had just been imported into Italy.

This is the much-quoted reference in the "Chronicles of Viterbo" (Viterbo, in Italy, is a little Northwest from Rome). Three such chronicles exist, all fifteenth century, each of which relies on an earlier chronicle for pre-fifteenth century records. (Further details of original sources in Mayer, 1971 [2]). These three chronicles all refer to what is evidently the same 1379 entry (now lost), which when reconstructed, must have read: "Anno 1379. Fu recato in Viterbo il gioco delle carte, che in Saracino parlare si chiama Nayb" ("In the year 1379 there was brought to Viterbo the game of cards, which in the Saracen language is called 'nayb'").

The word for playing cards used in the Italian Renaissance (naibi) and in Spain even today (naipes) is of Arabic origin and obviously derived from nā’ib. This Arabic word "nayb" does not mean 'playing cards', however, but "deputy" or "viceroy" (i.e. "Jack" or "marshall"), and is the name of the second and third court cards in the Mamluk pack. This suggests that the Italians couldn't pronounce the Arabic word for playing cards, which is "kanjifah", but found the word "nayb" easier, and so it caught on. This word also turns into the Spanish word "naipes" which is used today.

The three surviving "Chronicle of Viterbo" manuscripts are: One written by Fra Francesco d'Andrea de Viterbo, O.F.M. An edition published by Francesco Cristofori in 1888, is based upon the original manuscript, said to be very difficult to read. This account ends in 1450, but a large portion was written in 1435. The relevant passage reads "Fu recato in Viterbo il gioco de le carte, che in Saracino parlare si chiama Mayb."

Another was written by Niccolo de Niccola della Tuccia (born 1400), and goes down to 1476. This was edited and published by Ignazio Ciampi in 1872 although allegedly relying on 17th and 18th century MMs. "Fu recato in Viterbo il gioco delle carte du un saracino chiamato Hayl" or "che in saracino parlare si chiama nayl."

A third, written by Giovanni de Juzzo de Covelluzzo (died 1480), which goes down to 1479, has not been published in its entirety. It has been quoted by Ciampi (above) and by Feliciano Bussi in "Istoria della Citta di Viterbo", Rome 1742: "Fu recato in Viterbo il gioco delle carti, che venne de Seracinia, & chiamasi tra loro Naib."

Discrepancies between these respective chronicles are due to mis-readings, mis-spellings and copyists' errors, and we can fairly safely reconstruct what must have been the original entry.

-

1379 CONSTANCE, SWITZERLAND

Reference to playing cards.

-

1379 BRUSSELS, BELGIUM

Gambling

The first documentary evidence of playing cards in Belgium occurs in the Audit Office Register in the State Archives in Brussels. It is dated 14 May 1379 and reads in translation: "Given to My Lord and Lady on the 14th day of May, to purchase a pack of cards: 4 peters, 2 florins, making 8 sheep". (Note: a 'peter' was a gold or silver coin bearing the effigy of the Apostle Peter. 'Sheep' was the nickname given to a gold coin stamped with an Agnus Dei (used in France, Flanders and Brabant). "My Lord and Lady" were Duke Wenceslas of Luxemburg and Duchess Joanna of Brabant). Further references to purchases of playing cards follow in the same account book, some made by one Ingel Van der Noet (cost: 2 sheep), some by Colin Creevers, another by a certain Geerard, etc. One may infer that card games were very popular at the court of Brabant.

They played for high stakes at the Court, and the account books reveal exactly how much they lost. This makes one suspect that, just as online poker is very popular today and easy to access, a veritable craze for card playing existed in certain circles during the 1370s and 80s.

Alexandre Pinchart, writing about the same story in 1870, cites an account book of Wencesles and Jeanne, who reigned in the old duchy of Brabant from the year 1355, that describes a fête held at Brussels in 1379 at which cards were played. On the 14th. of May, 1379, the receiver general of Brabant gave to Monsieur et Madame four peters and two florins, valued at eight and a half moutons, to purchase a pack of cards, "quartespel mette copen". It is believed that this was a pack of 78 hand-painted cards on parchment, probably worked with gold. On the 25th June of the same year he paid some more money to Ange Van der Noel for a game of cards that the duchess had bought from him.

On August 28th 1380, there is paid by order of Jeanne to a certain master who had delivered "three pairs of cards" a sum of two old half crowns. On November 21st following, one of the servitors of the duchess received a florin for the purchase of a similar game. The cost of a pack of playing cards seems to be going down during the course of these purchases, perhaps cheaper cards were available as well as expensive hand-painted ones. The new phenomenon of gaming with playing cards would have given craftsmen an opportunity to satisfy the demand and make profits. There are apparently more such entries concerning both the duke and the duchess for sums of money spent on cards.

-

1380 BARCELONA, SPAIN

InventoryThe inventory, dated 26th October 1380, kept by the Barcelona merchant Nicolau Sermona, who lived in St. Daniel's alley (Callejon San Daniel), lists " unum ludum de nayps qui sunt quadraginta quatour pecie" ("a game of cards (naips) of 44 pieces"). A pack contaning 44 cards is unusual and may have been incomplete. However, 'normal' packs usually contained 52 cards, 48 cards, 40, 36 or even 32 cards, which are all multiples of 4. So why not 44 cards? Perhaps there was an old card game which used packs containing 1 - 8 plus 3 court cards. We do not know when and where he had obtained the cards, only that they may have been in his possession for some time.

The reference is found in two versions: 1) in the inventory of goods and 2) in the executor’s account (Llibre de Marmessoria). In the second entry the number of cards was originally given in numerals xliiii which are crossed out and replaced in writing.

Above: detail from “Llibre de la marmessoria de Nicolau Sermona”, Barcelona, October 1380, (AHPB 34/22, f.14) mentioning the pack of playing cards.

Above: detail from “Llibre de la marmessoria de Nicolau Sermona”, Barcelona, October 1380, (AHPB 34/22, f.5v) mentioning the ludum de nayps. Source: Col·legi Notarial de Catalunya Llibre de la marmessoria de Nicolau Sermona►

The name of Nicolau Sermona also occurs in earlier records in connection with his commercial activities. He had been involved in financing trading expeditions between Barcelona and near eastern destinations within the Mediterranean basin since 1349. Goods mentioned include Catalan fabrics, silver, honey, rice, oil and almonds, and Eastern spices, nuts and fruits. Although he himself may not have travelled on these expeditions, the seamen he employed could quite possibly have returned with some eastern playing cards in their personal luggage, which served as models for Western artisans to copy. Perhaps such a pack was gifted to Nicolau Sermona by a ship's captain. (Jean-Pierre Garrigue, 2015, pp.43-46).

-

1380 (circa) RODRIGO BORGES, PERPIGNAN, FRANCE

CardmakersDescribed as "pintor y naipero", the earliest named card-maker (we assume these were hand-painted cards, not yet printed), this reference occurs in several books on playing card history, but the original documentary source cannot be verified. Jean-Pierre Garrigue (2012, p.19 ff) has searched for this reference in the Archives Départementales des Pyrénées Orientales and notary records but was unable to find it. However, he did find evidence of a cluster of Catalan cardmakers and other artisans working in the Barcelona/Perpignan region, starting with Ferrando de Burgues, cardmaker, 1380. Other cardmakers include Joan Cassanyes, 1419; Joan Lehonart, 1432; Antoni Borges 1438-1466; Daniel Bassarola, 1439; Nanton Borges 1460-1470; Pera Borges. A Rodrigo de Borges, nahiper o pintor, was recorded in 1494. Others such as Guillem Burges and Bernardo Borges were weavers or cloth merchants. Note: spellings varied depending on whether they were recorded in Castilian, Latin or Catalan.

Above: the domains of the Crown of Aragon and the sites of the Catalan consulates in the Mediterranean in 1385 are marked in red. Some consulates worked to defend the interests of the local merchants in foreign cities.

The Kingdom of Valencia also supplied new goods with Arab roots, such as paper from Xàtiva. The most important hubs of catalan commerce were the capitals of the three Catalan-speaking regions within the Crown of Aragon, namely Barcelona, Valencia and Mallorca. Perpinyà can be included as a hub as well, as it was well-connected via land routes. Its maritime commerce took place via numerous ports and commercial hubs. The entire Maresme as far as Barcelona was highly active in maritime commerce near the end of the 15th century (Ferrer 2011).

Above: detail from the altarpiece of the Trinity (1489) attributed to the Master of Canapost which depicts the exchange of Perpignan. Museu Hyacinthe Rigaud, Perpignan.

Artisans involved in commerce with other craftspeople used related materials, pigments and decorative techniques, and also frequented the same market places, trade guilds and taverns. For example, tailors making doublets and other clothing may well have worked alongside cardmakers at trade fairs and had adjacent market stalls. Their clients also would have taken an interest in other wares being sold nearby, such as playing cards for recreation. A picture emerges of the worlds of fashion and leisure overlapping and complementing each other in the late middle ages and early Renaissance, and of artisans diversifying and adapting to the demand from customers.

-

End of Fourteenth Century — Block Printing

Above: playing cards spread through Europe at the same time as the earliest religious prints, which began to be printed from woodcuts late in the 14th century. An edict of the Council of Venice dated 1441 (see below) indicates that the card printing industry was already being undermined by outside competition.

Beginnings of block printing in Europe.

"Inasmuch as one of the first forms of block printing known in Europe—perhaps the very first form of printing on paper—was the making of playing cards" — T.F Carter

Religious prints began to appear around this time, printed from woodblocks and coloured by hand or using stencils. The technique was soon taken up by card-makers and marked a turning point towards mass-production and hence their being noticed by the authorities. The prime material (paper) was by now inexpensive, and a demand had arisen for the new game of cards which had recently arrived from the Islamic world.

It was the development of paper which made book printing a viable enterprise and in turn opened the way for the great age of expansion and discovery which would follow later in the 15th century. For more detailed account, see T.F Carter (1931) chapter 21.

At a practical level, producing cards from woodblocks is easier if packs contain 40 or 48 cards (2 x 24) rather than 52 cards, unless the pip cards are produced separately using stencils. For this reason, after the early 1400s Spanish-suited packs tended to drop the 10s and run from 1-9 plus 10, 11 and 12 as the three court cards. This sort of practical consideration may have led to the invention of the French suit system where the 12 courts could be printed from one woodblock while the 40 numeral cards were produced with stencils - a considerable saving of labour.

-

1380 NUREMBERG, GERMANY

References to playing cards.

-

1381 MARSEILLE, FRANCE

The notarial archives speak of nahipi which means ‘playing cards’.

-

1382 LILLE, FRANCE

ProhibitionAn ordinance of the city of Lille, dated 1382, when Lille belonged to France, forbade various games including dice and "quartes" (an early word for cards, in distinction from nahipi as used in the 1381 reference).

-

1382 NURENBERG, GERMANY

References to playing cards.

-

1382 BARCELONA, SPAIN

ProhibitionThe special Register of Ordinances in the historical archives of the city of Barcelona, for December 1382, includes a text prohibiting several games, including dice and cards, to be played in the house of a certain town official, subject to a fine of 10 "soldos" for each offence. It would take another 70 years or so for treasury authorities to raise revenues from playing cards by imposing taxes on their sale.

-

1384 VALENCIA, ITALY 23rd June

"Un nuevo juego llamado de los naipes" ("a new game called naipes") was prohibited by the Consul General of the city, as though it had only recently come to official attention.

-

1389 ZURICH, GERMANY

References to cards.

-

1390 VENICE, ITALY & HOLLAND

References to cards.

-

1390 GERMANY

In this year the first paper mill was established near Nuremberg.

-

1391 AUGSBERG, GERMANY

Reference to cards.

-

1392 JACQUEMIN GRIGONNEUR

CardmakersHe was paid 56 "sols Parisis" for three packs of gilded cards, painted with divers colours and several devices, to be carried to the king for his amusement. This oft-quoted reference is an extract from the 1392 accounts of Charles Poupart, treasurer to Charles VI, and for some time was believed to refer to the so-called "tarot of Charles VI" or "Grigonneur tarot" in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, because of M.C. Leber's suggestion in 1842 to that effect.

Doubtless stimulated by the high prices obtained for beautiful cards by the illuminators and miniature painters, engravers and carpenters, as well as other start-ups, must have contrived means of producing these items as well, thereby securing for themselves a share of the business. We can imagine how many technical innovations, perfected over time, may have led to the development of this new industry.

-

1392 FRANKFURT-AM-MAIN, GERMANY

Reference to cards.

-

1393 ITALY

References to children playing cards.

-

1393 DIJON, FRANCE

CardmakersEarliest reference to a woodcutter doing work probably intended for printing is a record of payment in 1393 (in the accounts for works in the Chartreuse of Dijon) to a certain 'Jehan Baudet, charpentier, pour avoir fait et taillie des moles et tables pour la chapelle de mon signeur audit Champmol dicte la chapelle des Angles, a la devise de Beaumez'. This 'tailleur de molles' was probably cutting his blocks for printing textiles for altar hangings or similar work, after designs by the painter Jean de Beaumetz. There are various other slightly ambiguous references probably to textile blocks, such as in 1327 and 1328 to 'tapis d'entailleure' and 'deus dras ovree de entailleure de brodures' by a certain Jehan Herenc of St. Omer; in 1391 payment at St. Omer to Johannes Cruspondere 'pro factura ymaginum lignearum'. Although there is ambiguity in these early references between sculpture and cuts for printing, the small fees paid suggest wood blocks.

-

1395 FEDERICO DE GERMANIA, BOLOGNA, ITALY

A certain Federico de Germania sold 'cartas figuratas ad imagines et figuras sanctorum' at Bologna. There is no proof that he printed his cards from blocks, but as the document concerned accuses him of coining false money, this makes it more likely that he was able to cut blocks. It is interesting to note that in France early woodcuts seem to have sometimes been regarded as 'malefacons' (i.e. contraband) in the eyes of the guild of imagiers

-

1395 AMSTERDAM, THE NETHERLANDS

Playing cards are authorised by an Amsterdam Charter (chess, ball games and cards) but were forbidden two years later in Leyden.

-

1397 ULM, GERMANY

Prohibition against cards.

-

1397 PARIS, FRANCE

On the 22nd January, 1397, the Prevot of Paris issued a decree forbidding working people to play at tennis, bowls, dice, cards and ninepins on working days. It can be pointed out that for cards to have become so popular and to be obtainable so readily by the working people, that a cheap and simple method must have been employed to manufacture them, and this is offered as possible evidence that printing must have been known about.

However, the most ancient cards which survive today are all hand painted, and records exist of other such cards being made, as well as for whom, and the price paid for them. The only references to cheaper varieties of cards are these prohibitions against their use, whilst the wealthy evidently were allowed to indulge.

-

1397 LEYDEN, THE NETHERLANDS

References to playing cards including a prohibition.

-

1398 ULM, GERMANY

Earliest reference to the term 'Formschneider' in German documents, but which possibly also refers to the cutter of blocks for textile printing and is no certain limit for the introduction of prints from woodcut on paper. Various early writers have speculated concerning where this habit of card-playing was introduced from. The foregoing evidence at least confirms the possibility that they were introduced from the East since the requisite techniques seem to have been known and practiced there for longer than in the European continent. We may very reasonably, therefore look for indications and evidence from such parts for their earlier existence.

-

14-15C DANIEL BARCELO, BARCELONA, SPAIN

Card-maker.

-

Above: fragment of Mamluk playing card, see more►

c.1400 EGYPT

GamblingA passage in Ibn Taghri-Birdi's "Annals of Egypt and Syria" (dealing with events of the year 1417-1418) mentions that the future sultan al-Malik al-Mu'ayyad won a large sum of money in a game of cards. This confirms that playing cards were known in Mamluk Egypt not long after they first appeared in Europe. The text reads:

"The reason for the seizure of the aforementioned Akba'i [the governor of Syria residing in Damascus] was that the Sultan al-Malik al-Mu'ayyad [reigned from 1412 to 1427] had, in the days when he was emir, purchased a youth for 2000 dirhams which he had won playing 'kanjafah' [or 'kanjifah']. Al-Malik al-Mu'ayyad was at that time a qa'id and he was playing cards with one of his comrades and had won many dirhams from this man. Then the aforementioned Akba'i was brought into his presence together with his dealer. He [al-Mu'ayyad] was taken with him and he purchased him. The dealer then sought out his [al-Mu'ayyad's] bursar in order to collect the price of the aforementioned Akba'i, but he could not find him; so al-Mu'ayyad himself paid him the price from the dirhams which he had won gambling…"

The name of the game -- 'Kanjafah' -- is apparently of Persian origin, and from this extract it can be seen that it was a gambling game involving high stakes. Al-Mu'ayyad was appointed emir in 1399, and elected sultan in 1412, and so the account refers to somewhere within these dates.

Prohibition

From the repeated municipal regulations forbidding card-playing, to be found in the Burgher-books of several cities of Germany, between 1400 and 1450, it would seem that the game was extremely popular in that country in the earlier part of the fifteenth century; and that it continued to gain ground, notwithstanding the prohibitions of men in office. There are orders forbidding it in the council-books of Augsburg, dated 1400, 1403, and 1406; though in the latter year there is an exception which permits card-playing at the meeting-houses of the trades. It was forbidden at Nordlingen in 1426, 1436, and 1439; but in 1440 the magistrates, in their great wisdom, thought proper to relax in some degree the stringency of their orders by allowing the game to be played in public-houses. In the town-books of the same city there are entries, in the years 1456 and 1461, of money paid for cards at the magistrates' annual goose-feast or corporation dinner.

From William Andrew Chatto: Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards, London 1848, Chapter 3, The Progress of Card-Playing. here►

-

1401 BARCELONA, SPAIN

InventoryAn inventory of Barcelona merchant Miguel Ça-Pila includes a pack of large cards, painted and gilded: “un joch de nayps grans, pintats é daurats tots, ab cubertes negres”. Like other merchants of his day, Miguel Ça-Pila was involved in financing trading expeditions around the Mediterranean, reaching destinations such as Cyprus, Egypt, Syria and other Islamic ports in the Levant. It is perfectly feasible that oriental cards reached Europe during such commercial exchanges. The pack of cards may have been in Miguel Ça-Pila’s possessions for some time before the inventory was made in 1401. The inventory is in the records of the notary Bernat Nadal, Barcelona.

-

1402 ULM, GERMANY

CardmakersEarliest documentary reference to the term 'Kartenmaler' or 'Kartenmacher' (painter or maker of playing cards). We can presume that the production of playing cards must have been a thriving industry, especially at Ulm, at the end of the XIV and beginning of the XV c. The probability of woodcuts having been used in their production by about 1400, or even earlier, cannot be disregarded, even though there are no surviving examples.

-

1403 RAIMUNDO DE SENTMENAT, SPAIN

During his stay at the Castle of Jerica, the King of Aragon (Martin the Humane) asked to be sent 'un Joch de naips'.

-

1404 SYNOD OF LANGRES, FRANCE

Religious BansLaurentii Bochelli, writing in 1609 in Decreta ecclesiae Gallicanae, relates that at the Synod of Langres in 1404 Cardinal Louis de Bar, Bishop of Langres, forbade the clergy from indulging in various games including cards.

-

1408

InventoryIn the inventory of the goods of LOUIS DE VALOIS and his wife Valentine, nee Visconti, Duke and Duchess of Orleeans, begun at the order of their son Charles on the day of his mother's death in 1408, there are listed "ung jeu de quartes sarrasines" and "unes quartes de Lombardie". Louis and Valentine were married in 1389, and she could have brought the cards with her from Milan then. Later examples of Lombard tarot packs reveal many similarities to Saracen cards in the suit sign styles, although there is no other evidence that they were in existence in 1408, let alone 1389. Here they are called 'quartes' and not 'tarots' in any case, which leaves us thinking that they probably were regular Italian playing cards. The concurrence of Islamic and European playing cards ('quartes') in lists of property such as this gives weight to the hypothesis of the Islamic origin of playing cards in Europe, and certainly to the fact of European/Muslim interchange as far as playing cards were concerned.

-

1412 BARCELONA, SPAIN

InventoryJean-Pierre Garrigue (2016, p.31 & p.48) describes a receipt drafted on 23 July 1412 by the notary Bernat Nadal between Maria, Llorenç Lledó’s widow, and the executors of his will, concerning “unum ludum nayporum” (a pack of cards). Llorenç Lledó was not a wealthy merchant, but a 'baixatoris,' the Latin form of the Catalan term 'abaixador,' a sheet clipper, who removes any excess or loose fibres from the surface of fabric. Although precision and expertise was required to ensure that the fabric maintained its quality while removing any unwanted wool fibres, the craft was usually associated with the middle class. Garrigue remarks that it is surprising that Llorenç Lledó could afford to own a set of cards valuable enough to appear in a will, but there is no further information regarding the type of cards or their provenance. Nevertheless this illustrates the high value of painted playing cards at this early date,

Above: extract of release written between Maria Lledó and the executors concerning “Unum Ludum Nayporum”, 23 July, 1412. Arxiu Historic de Protocols de Barcelona, 58/180.

Note on Quality and Value Vellum and parchment were replaced with paper by around 1350, so the earliest playing cards were mainly made on paper. The quality of these cards depended on several factors, with one crucial aspect being the type and quality of paper utilized. Expensive, high-quality, stiff paper was favoured for crafting premium playing cards, while lower-grade cards were often made from older or more affordable paper. Merchants, who were well-versed in recognizing and appreciating quality, were particularly attuned to the craftsmanship of playing cards. As a result, high-quality decks found their way into inventories and were mentioned in wills.

-

1414 BARCELONA, SPAIN

InventoryTwo distinct Barcelona inventories have entries "j joch de nayps (or 'nahyps') moreschs". This tallies with the 1379 reference (above) that Arabic or Saracenic playing cards had just been imported into Italy. Muslims, Christians, and Jews coexisted at this time in a society enriched by Islamic culture, which influenced daily life. An example of 'Moorish playing cards' has been discovered in Barcelona: A Moorish Sheet of Playing Cards

-

1419 JOAN CASSANYES

Cardmakers"Nahiperius" catalan cardmaker working in Perpignan, also referenced as a cardmaker in his son's marriage certificate in 1435. A Rafael Cassanyes is recorded as a cardmaker in Perpignan in 1491 suggesting a possible dynasty (Jean-Pierre Garrigue, 2012, p.26).

-

1421 JAIME ESTALOS

Cardmaker"Grabador de naipes". This sounds more like an engraver rather than a painter of cards.

-

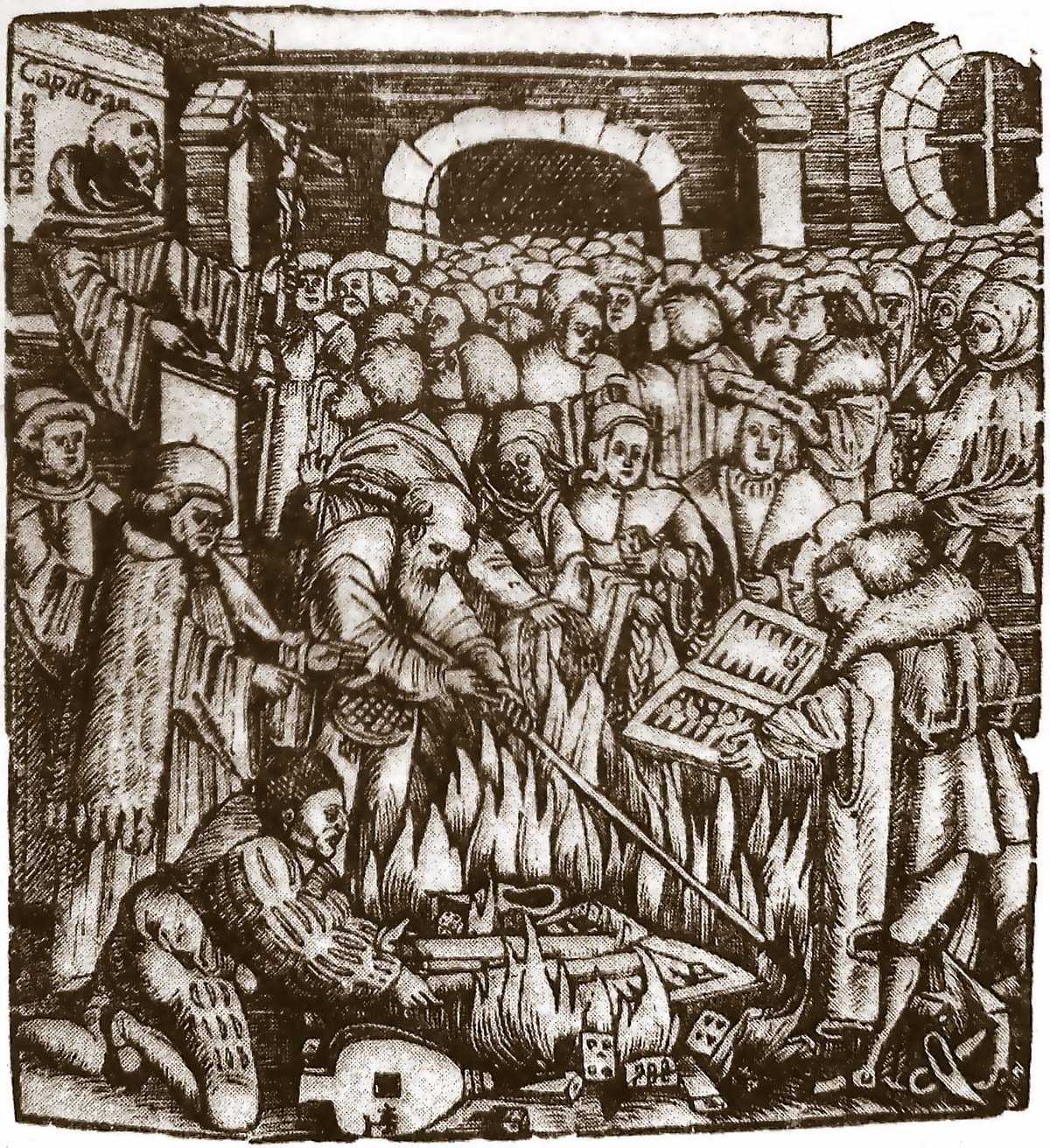

1423 ST BERNADIN OF SIENA, ITALY

Religious Ban"Charticelles seu Naibos" sermon. Bologna appears to have been a hotbed of gambling in the early XV c., and it needed St. Bernardino to persuade players to burn their cards. He preached at the church of San Petronio, Bologna, against the vices of gaming in general and playing cards in particular.

He spoke of a pack of 56 cards, including queens, without mentioning atutti, suggesting either that they did not exist, or were acceptable.

He spoke of a pack of 56 cards, including queens, without mentioning atutti, suggesting either that they did not exist, or were acceptable.

The story goes that when hearers threw their cards into the fire, a card-maker who was present and heard the denunciations even against those persons who supplied the obnoxious article, exclaimed: "I have not learned, father, any other business than that of painting cards, and if you deprive me of that, you deprive me of life and my destitute family of the means of earning a subsistence." To this the Saint replied, "If you do not know what to paint, paint this figure, and you will never have cause to repent having done so", and showed the card-maker the figure of a radiant sun, having in the centre the sacred monogram I.H.S.

See: original story here►

Above: a climax was reached in 1423, when a famous sermon against card playing was preached by St. Bernard of Siena from the steps of St. Peter’s in Rome, with the result that his hearers rushed to their houses, brought such cards as they possessed to the public square and burned them.

-

1423 NUREMBERG, GERMANY

CardmakersCard-making was a regular trade in Germany in the fifteenth century, and the terms 'Kartenmacher' and 'Formschneider' are used distinctively, sometimes entered on the same page of civic archives. There was, then, a distinction between these vocations, although the followers of each business perhaps belonged to the same guild or company. In some towns the term 'Formschneider' does not occur at all in the XV century, suggesting that block-cutters had no special guild, but belonged to the larger class of carpenters.

-

1425 Catalonia, SPAIN

Primitive Latin suited pack, possibly produced in Catalonia, dated by paper analysis as early XV century, which makes this one of the earliest known surviving packs of playing cards. Learn more here...

Above: cards from a primitive Latin suited pack, possibly of Catalan manufacture. There are Moorish influences in some of the cards: see the double-panelled Saracenic shield on the cavalier of swords more...►

-

1427 TOURNAI, BELGIUM

CardmakersTournai was a centre of the arts, where numerous artists and craftsmen resided. Many of these also made playing cards for the then flourishing trade.

In 1427 two master card-makers in Tournai, Michael Noel and Philippe du Bos were admitted as masters in the painters' guild. They each registered his chosen mark: one was a rose, the other a wild boar. Each master card-maker had as his helpers those who prepared the colours, les broyeurs; those who applied the colours, les bruneteurs or licheurs en couleurs (mixers of colours); and those who prepared the paper, les carteurs. Their duties were clearly defined by the rules of the guild, which also stipulated which colours were to be used. The relatively large numbers of masters and apprentices recorded in the guild registers in the latter fifteenth century suggest that card making must have developed into a sizeable local industry. The register contains the names of many women who worked in the industry.

1427-31 STUTTGART HUNTING PACK Numerals 1-9, banner 10's, 3 courts per suit. Total = 52 cards. In the suit of stags and dogs the courts are all ladies, she corresponding to the under valet stands in a garden, and the queens are seated on thrones. The suits of ducks and falcons are all men, princes and mounted kings. The valets are reminiscent of the pages in the Goldschmidt/Guildhall cards. The numeral cards do not appear to have been copied from a pattern in quite the same way as the Master of the Playing Cards, since each figure is individual.

1427-31 STUTTGART HUNTING PACK Numerals 1-9, banner 10's, 3 courts per suit. Total = 52 cards. In the suit of stags and dogs the courts are all ladies, she corresponding to the under valet stands in a garden, and the queens are seated on thrones. The suits of ducks and falcons are all men, princes and mounted kings. The valets are reminiscent of the pages in the Goldschmidt/Guildhall cards. The numeral cards do not appear to have been copied from a pattern in quite the same way as the Master of the Playing Cards, since each figure is individual. -

1428 MIGUEL DE ALCAYNI

CardmakersMiguel de Alcayni and the sons of the painter BARTOLOME PEREZ, all from Valencia, received a commission from Queen Maria, wife of Alfonso the Magnanimous, to draw, paint and finish off a pack of cards. At the same time, the queen sent payment for the paper that would be necessary.

-

1429-56 DIEGO ALFONT

CardmakersValencia JUAN ALVAREZ " Cardmakers.

-

1430 ANTONIO DI GIOVANNI DI SER FRANCESCO

Cardmakers'Pittor di naibi' of Florence. Whilst filling in his income-tax returns, he mentions amongst his property 'wood blocks for playing-cards and saints'.

-

1434

Queen Mary (already referred to under 1428) is recorded as having received a small box with a very beautiful pack of cards, offered to her by the mercer Miguel de Roda. (A mercer was formerly a dealer in small wares, although later became a dealer in cloth or silks).

-

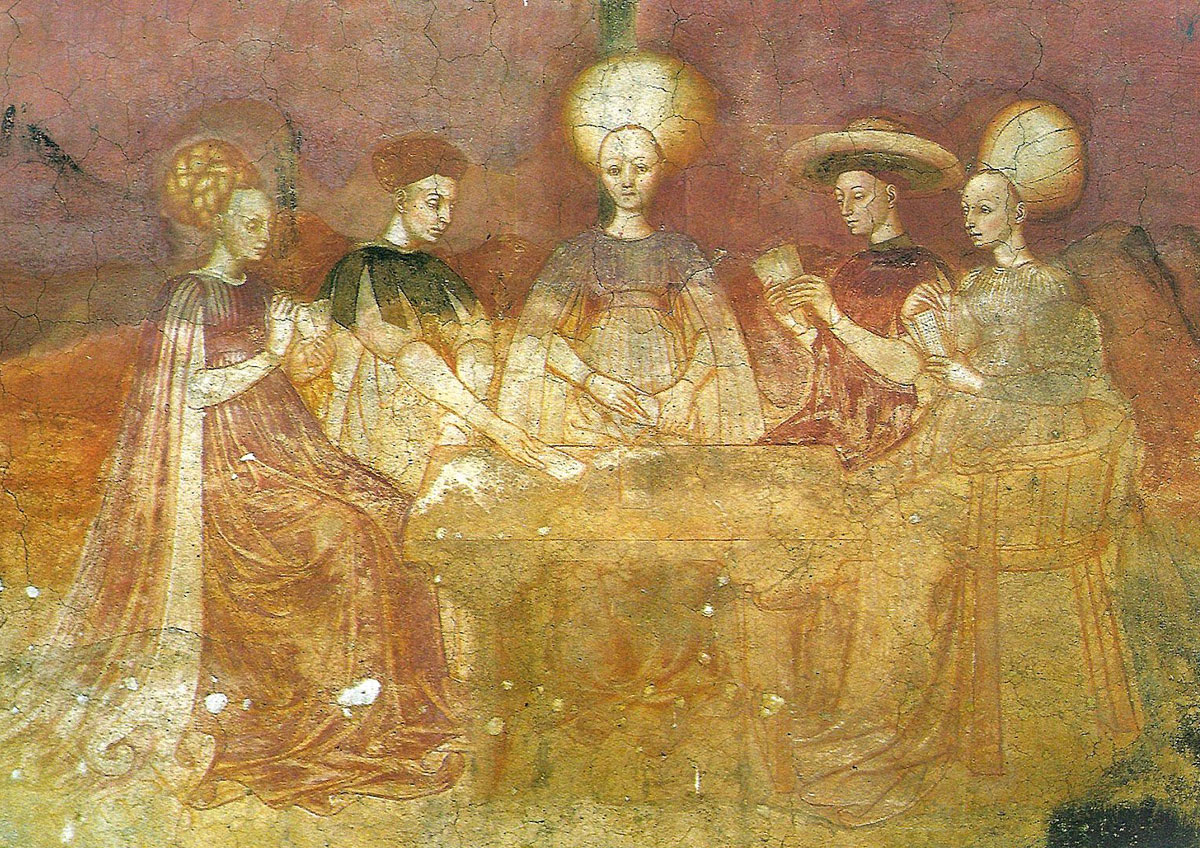

c1435 FRESCO BY PISANELLO

CardmakersCard playing in the court of Prince Borromeo.

Above: the Tarocchi Players of Casa Borromeo, Milan 15th C.

-

1438-66 ANTONIO BORGES, BARCELONA

Cardmakers -

1439 BARCELONA, SPAIN

InventoryAn inventory entry of this year records "x jochs de naips moreschs; iij altres jochs de naips plans petits". Some form of "moorish", Islamic or Mamluk-type playing cards were evidently well-known in Spain at this time. See also 1414 (above).

-

1439 DANIEL BASSAROLA, Barcelona & Perpignan

CardmakersSeveral cardmakers (nahiper) of this name are recorded in Perpignan and Barcelona between 1439-1482 (Jean-Pierre Garrigue, 2012, p.24).

-

1440 PROMISE (vow or pledge) not to play games.

Daniel Bassarola, cardmaker from Perpignan, "promises and swears by mouth and hands in the presence of Blasius Ros, royal gatekeeper of Perpignan, that from now for the next two years he will not play or cause to be played any game of any kind, and if he breaks this promise, he shall be considered a perjurer and a fraud according to the customs of Aragon, the usages of Barcelona, and the general constitutions of Catalonia." (Jean-Pierre Garrigue, 2012, p.25). Promises such as this, formalized through notarial protocol, reflect early societal and religious efforts to regulate behaviour, maintain communal standards and discourage activities perceived as sinful or morally questionable. Given that Bassarola was a cardmaker, he needed to navigate his role and responsibilities within the prevailing societal norms and expectations, at the thime when card-playing culture was burgeoning in Europe. This is one of the earliest documented pledges of its kind.

-

1440 STRASSBURG, FRANCE

CardmakersA certain Johann Meydenbach is referred to specifically under the two crafts of 'Briefmaler' and 'Formschneider'. 'Briefmaler' means the painter or illuminator of short documents, a lower class in the hierarchy of illuminators of manuscripts, and is unlikely to have been used loosely to include cutter of woodblocks. There was probably less distinction between the 'Briefmaler' and the 'Kartenmaler', the latter being perhaps the lowest class of illuminator.

-

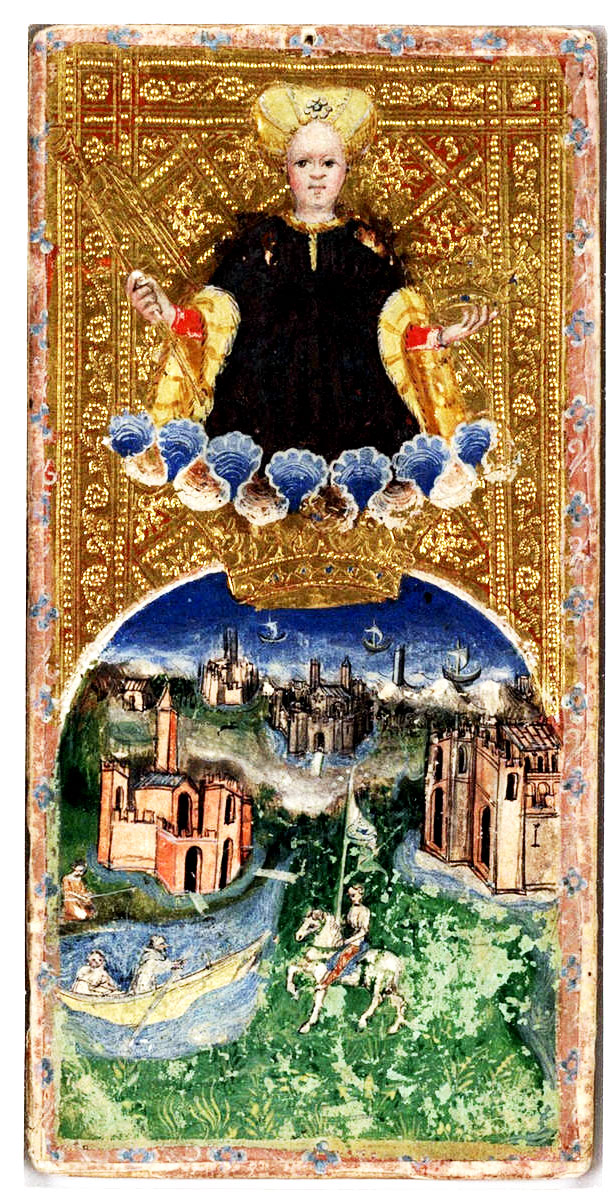

1440 MILAN, ITALY

Around 1440 Decembrio, the official biographer of Filippo Maria Visconti, third duke of Milan, wrote that the duke enjoyed playing at a game that used painted figures. Decembrio also wrote that duke Filippo paid 1500 gold pieces to Marziano da Tortona for a pack of cards decorated with images of Gods, emblematic animals and figures of birds.

Marziano da Tortona is alleged to have painted the 'Visconti di Modrone' pack of tarocchi cards.

-

1441 VENICE, ITALY

CardmakersWoodcutters and makers of playing cards, in a request to the Council of the city, ask for protection against the foreign import which they declared had ruined their trade. As a result, regulations were made forbidding the import of every kind of print, including textiles and cards, under penalty of forfeiting such articles and being fined. This order appears to have been aimed at German card makers.

"mccccxli. Oct 11. Whereas the art and mystery of making cards and printed figures, which is used at Venice, has fallen to total decay; and this in consequence of the great quantity of playing cards, and coloured figures printed, which are made out of Venice; to which evil it is necessary to apply some remedy; in order that the said artists, who are a great many in family, may find encouragement rather than foreigners. Let it be ordered and established, according to that which the said masters have supplicated, that, from this time in future, no work of the said art, that is printed or painted on cloth, or paper, that is to say, altar pieces (or images) and playing cards, and whatever other work of the said art is done with a brush and printed, shall be allowed to be brought or imported into this city, under a pain of forfeiting the works so imported, and xxx livres and xxii soldi; of which fine one third shall go to the state, one third to the Signore Giustizrieri Vecchi, to whom the affair is committed, and one third to the accuser. With this condition, however, that the artists, who make the said works in this city, may not expose the said works to sale in any other place but their own shops, under the pain aforesaid, except on Wednesdays at S. Paolo, and on Saturday at S. Marco, under the aforesaid penalties." Then follow the subscriptions of the Proveditori del Comune, and Signori Giustizieri Vecchi.

All this goes to show that the playing-card business must have been flourishing for some while before this date, in order for it to be described as "fallen to total decay". We have several earlier dates pointing to the existence of cards and of knowledge of printing techniques in general in Venice and Italy from 1379 onwards.

-

1440-50 AMBRAS HOFJAGDSPIEL

'The pack of Princely Hunting Cards of Ambras'. 56 cards: numerals 1-9 + banner 10's. Four courts per suit, mounted kings and queens, upper and under knaves. Falcons, herons, hounds and lures. Attributed to Konrad Witz and his workshop at Basle.

-

1443 BERNARDO SOLER

Cardmakers"Grabador de Naipes".

-

1443 JUAN BRUNET

CardmakersA catalan card-maker recorded as being a member of the "Cofradia de los Merceros" ("Union" or "Guild of Mercers" or "Haberdashers") before amalgamation with the playing card makers.

-

1444 LYON

CardmakersThere are numerous records of 'Tailleurs de molles de Cartes' at Lyon from 1444.

-

c.1446 MASTER of the PLAYING CARDS

CardmakersNumerals at least up to nine, with four court cards per suit. Lions/bears, wild people, antelopes, birds. Seated kings and queens, ober and unter knaves. The fact that these are engraved may indicate the greater estimation in which line-engraving was held than woodcut.

-

1449 ISABELLE OF LORRAINE

A series of 16 cards is described in a letter dated 1449 from Jacobo Antonio Marcello, a servant of King Rene of Anjou, to Isabelle of Lorraine, first wife of King Rene.

-

1449-53 ARNALDO BRU, Barcelona

Cardmakers -

1450 DAS GULDIN SPIL

The Dominican Meister Ingold, who in 1450 wrote a work in the Alsatian dialect called "Das Guldin Spil", lists the four suits as Roses, Crowns, Pennies and Rings.

-

15th Century

CardmakersAlejandro Bussero, Ramon Esquert, Miguel Fabra, Miguel Ferrer, Martin Gallart, Pedro de Laredo, Francisco Lleonart, Antonio Pelegri, Bartolome de Primerant, Miguel Sanz, Ramon Veya, recorded as card-makers from Barcelona during the fifteenth century. There was also the Borges family, from Rosellon, as well as several Castilian, Andalucian and French card-makers. There was clearly a lot of movement and interaction between artists and craftsmen in this region.

-

1456 RODRIGO PADROLO, Barcelona

Cardmakers -

1457 TREATISE OF THEOLOGY

Religious BansWritten by Saint Anthony, Bishop of Florence, refers to playing cards and Tarot, thus suggesting that they were separate games.

-

1460 BARCELONA

InventoryAn inventory entry reads: "jochs de nayps plans, y altres jochs moreschs".

-

1461 REGENSBERG

CardmakersA certain Wenczl is noted in records as 'Maler' and 'Aufdrucker' at Regensberg.

-

1463 PARLIAMENT ROLLS

ProhibitionIn the third year of Edward IV, (March 4, 1463 to March 3, 1464) a statute was issued prohibiting, as from the following Michaelmas day (Sept, 29, 1464) the importation into England and Wales of various "chaffares, wares, ou choses desoubs escriptes." The "chaffares, wares, or things written below" were numerous and miscellaneous, including fire-tongs, dripping pans, dice, tennis balls, pins, pattins, pack-needles, painted wares, daggers, woodknives, bodkins, tailor's shears, razors and "Cardes a jouer."

-

1464 BASLE

CardmakersReference to Lienhart Ysenhut, Heiligenmaler, Briefmaler and Kartenmacher.

-

1465 PRINTING PRESS

InventoryIn the inventory of a certain Jacoba von Loos-Hensberge who died in the Bethany convent at Malines in 1465, are mentioned a press for printing wood blocks, nine wood blocks for printing images, with 14 other stone blocks (or small stone stamps).

-

c.1470 MASTER P.W's CIRCULAR CARDS

Cardmakers

Cologne. Total of 72 cards. 1-10, ober and unter, mounted kings and queens in roses, carnations, rabbits/hares, parrots and columbines. Plus two extra cards. Whilst the kings and queens are mounted, the knaves are differentiated by the upper or lower placing of their suit signs, and by the fact that the upper one is running and the lower one standing. There are various copies of this set of cards, and sometimes cards within the same set appear to have been made by different engravers. Furthermore, ther have been disagreement regarding the precise composition of the pack, some people reckoning it only to have consisted of numerals 1-9, or in four suits instead of five.

-

1470-1519 PEDRO BORGES, BARCELONA

CardmakersAnother member of this dynasty of card-makers (see above 1380).

-

1474 JOAN SANT CLIMENT

CardmakerJoan Sant Climent of Valencia, Spain, was a card-maker and a poet. He is recorded to have participated in a literary competition with a work entitled "Trobes en llaor de la Verge Maria" which became the first work printed in Valencia.

-

1474 ULM

A manuscript chronicle states that: 'playing cards were sent in large bales into Italy, Sicily and other parts by sea' in return for spices and other merchandise. Ulm was another city that produced remarkable woodcut books, as well as playing-cards.

-

1475 BAPTISTA PLATINA

Writing in his treatise De Honesta Voluptate, recommends cards as a beneficial after-dinner game for gentlemen, to divert their minds and thereby improve digestion. He warns against cheating or desiring to gain anything.

-

1476

ProhibitionReference to a prohibition of dice and card games by Ferdinand and Isabella, referring to the kingdom of Castilla. Apparantly this is the first genuine reference to cards in that area (as distinct from Catalunya).

-

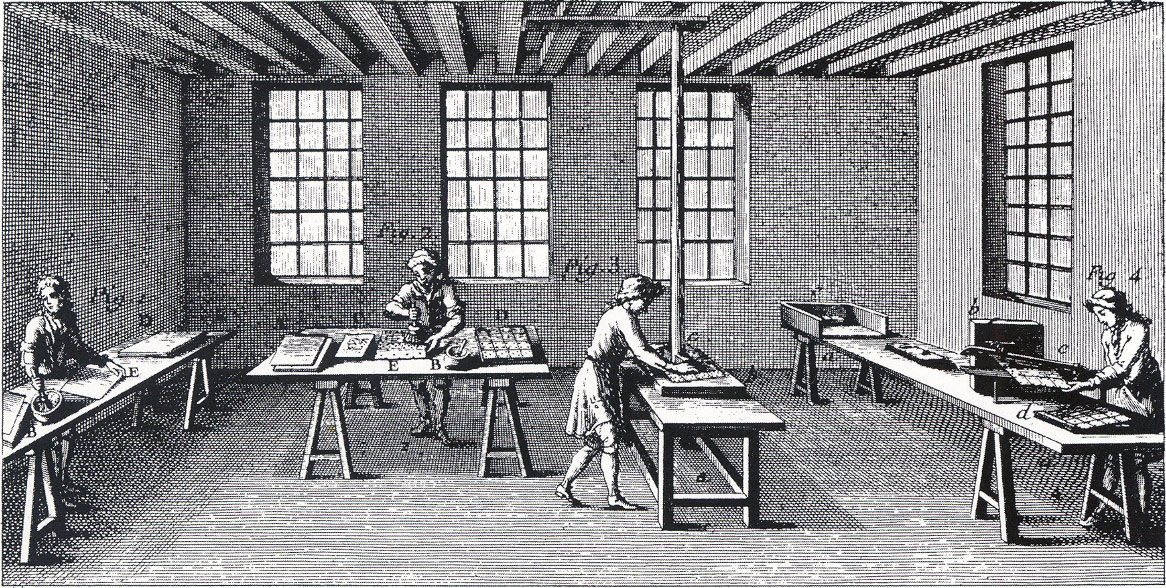

A 1480 document

sets forth numerous technical regulations governing the card makers of the Tournai guild (Belgium). Cards were printed or stencilled on bleached and browned paper pasteboard and painted with distemper in colours such as scarlet, vert-de-gris, white and black. The use of gold, silver or azure required an extra payment to the guild.

-

1492

Christopher Columbus reaches the Americas.

-

1534

It’s been recorded by Garcilasia de la Vega that “the soldiers of the Spanish expedition of 1534 played with leather cards”.

-

1536

Printing was first practised in the New World in the city of Mexico, by Juan Cromberger, or his agent [Juan] Pablos, between 1536 and 1540.

-

1605

Many card games developed in the 17th century one of them being "Veintiuna". The first written reference is to be found in a book of Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote, and a gambler himself. The main character of his tale is proficient at cheating at "veintiuna" (Spanish for twenty-one), and stated that the object of the game is to reach 21 points without busting. This short story was written between 1601 and 1602, so the game was played in Castilia since the beginning of the 17th Century or even earlier. Later references call veintiuna the game blackjack and that is the name used today.

-

1990

Playing cards become digital and with the growing popularity of the PC more people are playing on their computers.

Religious Bans The Church

The Church took a strict, prejudicial view on what it saw as lewd, frivolous, fickle or dishonest behaviour. Members of the clergy would certainly not approve of card playing if it had anything to do with gambling or fortune telling. Moralising tracts were published expressing disapproval of gambling as a mortal sin which might offend God and destroy lives.

Laws and royal decrees were passed forbidding card games from an early date, most likely directed at gambling and immoral behaviour including card sharping and swindling. But these were to no avail as the games were so popular. The authorities began to realise that playing card production had to be be controlled by an official bureaucracy, or in many cases playing card monopolies were set up and taxes raised for the treasury.

Wherever in Western Europe man turned his eyes, he was confronted by the majesty of the church. Everything he did was approved or disapproved, blessed or cursed, interpreted and solemnised by the Church. He was baptised by it, married by it and buried by it. He called on angels, saints and martyrs for help, visited shrines and holy wells, made oaths on sacred relics. The Church dominated men’s minds and imagination... more →

Above: playing card from c.1465 by a German engraver, goldsmith, painter and printmaker known as the Master E.S. (c.1420-1468).

Above: Everyday life in the late Middle Ages, woodcut, Augsburg, 1472. Austrian National Library 009116►

Above: card players, woodcut, Constance, 1479. Austrian National Library 006763►

Above: interior view of playing card workshop where colouring, polishing and cutting operations are taking place. Many of these artisanal skills would later be lost or automated with the advent of steam powered machinery. Learn more →

Above: card playing continued to flourish and spread throughout Europe, in spite of legal ordinances against gambling as well as religious moralising against card playing which were of no avail.

References

- Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, F IV 43, f. 1r – Johannes von Rheinfelden, Tractatus de moribus et disciplina humanae conversationis: id est ludus cartularum moralisatus

- Carter, Thomas Francis: The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward, New York, Columbia University Press, 1925, 1931.

- Dummett, Michael: The Game of Tarot: From Ferrara to Salt Lake City, Duckworth, 1980

- Escartín González, Eduardo: Estudio Económico sobre el Tratado de Ibn Abdún, Fundación El Monte, Sevilla, 2006 online here►

- Farley, Helen: A Cultural History of Tarot, published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

- Ferrer, Maria Teresa: Catalan commerce in the late Middle Ages, published in 2011 by Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona.

- Ferro Torrelles, Víctor: Registro de Naiperías Españolas, Asescoin, undated

- Garrigue, Jean-Pierre: La Carte à Jouer a Perpignan du Moyen-Âge a nos jours, Sociéte Agricole, Scientifique et Littéraire des Pyrénéees-Orientales, 2012

- Garrigue, Jean-Pierre: Le Carte à Jouer en Catalogne XIV & XVI siècles, Les Presses Littéraires, 2015

- Ibn ’Abdūn, ed. Lévi-Provençal, Tratado de Hispa, Talās rasā'il andalusīya, 52-3 / Tr. García Gómez y Lévi-Provençal, Sevilla a comienzos del siglo XII: el tratado de Ibn ’Abdū Madrid, 1948, 161-2 (no.179 & 182).

- Mayer, L.A. Mamluk Playing Cards, ed. R. Ettinghausen and O. Kurz, Leiden, 1971. This treatise was originally published in the Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Le Caire, XXXV!!!, 1939, pp. 113-118.

- Sandrock, John E.: Ancient Chinese Cash Notes - The World’s First Paper Money

- Low De Vinne, Theodore: The Invention of Printing

- de la Vega, Garcilasia: Historia de la Florida, published Madrid in 1723.

- Jaume March (1334/1335–1410) was a Valencian language poet

By Simon Wintle

Member since February 01, 1996

Founder and editor of the World of Playing Cards since 1996. He is a former committee member of the IPCS and was graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal for many years. He has lived at various times in Chile, England and Wales and is currently living in Extremadura, Spain. Simon's first limited edition pack of playing cards was a replica of a seventeenth century traditional English pack, which he produced from woodblocks and stencils.

Related Articles

Agatha Christie and card games

Agatha Christie uses card-play as a primary focus of a story, and as a way of creating plots and mot...

Rouen Pattern - Portrait Rouennais

An attractive XV century French-suited design from Rouen became the standard English & Anglo-America...

Paris 2024 Olympics 3

Paris Games mascot Phryge engaged in different sports in a Happy Families-type game.

Paris 2024 Olympics 2

A standard French Tarot game pack with passing references to the Paris 2024 Summer Olympic Games.

Paris 2024 Olympics 1

Modern Paris pattern courts, special ace and jokers for the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris.

Playing cards with prints by Sumio Kawakami

Woodblock print designs created by Sumio Kawakami in 1938-9, each card having a different illustrati...

Ganjifa - Playing Cards from India

Indian playing cards, known as Ganjifa, feature intricate designs with twelve suits and are traditio...

The Henry Hart Puzzle

Explore the intricate history and unique design variations of Henry Hart's playing cards, tracing th...

Sevilla 1647 reproduction

Facsimile of Spanish-suited pack produced in Sevilla, Spain, 1647.

Why our playing-cards look the way they do

Analysis of early playing card designs: origins, suit differences, standardization, technological ad...

Introduction to Collecting Themes

Playing cards can be broadly categorised into standard and non-standard designs, with collectors app...

Victor Hugo 1885-1985

Characters from novels by Victor Hugo marking the centenary of his death, as conceived by Dominique...

Victor Hugo “L’homme qui rit”

Two different packs with costume designs for Victor Hugo plays, issued on the centenary of his deat...

Le Monde Primitif Tarot

Facsimile edition produced by Morena Poltronieri & Ernesto Fazioli of Museo Internazionale dei Taroc...

Les plaques émaillées d’Antoine Vollon

54 different enamel plaques depicting silk manufacture, by the Lyon artist Antoine Vollon.

Pinocchio playing cards

Comic book drawings inspired by Carlo Collodi’s children’s classic, Pinocchio.

Trending Articles

Popular articles from the past 28 days