Russian Playing Cards

Playing cards were known in Muscovy as early as the last quarter of the sixteenth century.

Although the history of playing cards in Russia is often associated with the establishment of the Russian Playing card manufactory in 1817 during the reign of Tsar Alexander I, playing cards were known in Muscovy as early as the last quarter of the sixteenth century. In the Dictionnaire Muscovite (1586) compiled by members of the first French expedition to the mouth of the Northern Dvina, playing cards were mentioned along with such games as zern’ (dice) and draughts. The Dictionnaire Muscovite remains the only document in which playing cards are mentioned in relation to Russia at the end of the sixteenth century.

A slightly later source is the dictionary by the English traveller Richard James who visited Kholmogory and Arkhangelsk in 1618–1619. That dictionary includes the names of Russian card suits and face cards at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

To date, there are no direct and accurate historical facts indicating the introduction of playing cards into Russia. Cards are believed to have appeared from the late 16th and 17th centuries from Germany and Poland and via the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Some argue for the Czech origin of Russian playing cards due to the linguistic similarities between the Russian and Czech terminology.

During the latter years of the reign of Peter the Great (c. 1689-1725) local playing card makers and factories began to appear, small in number at first but increasing after 1761 when Empress Elizabeth regularized card games and divided them into legal games of skill and illegal games of chance, or gambling. Legal card games were those where the outcome depended not only on chance but also on the intellect and the skill of the player while gambling games included those where the outcome was determined entirely by chance and were strictly prohibited.

Cards were first branded/stamped in Russia in 1765 when a tax was imposed on both imported and home-produced packs, with the revenue collected going to foundling hospitals. These hospitals, together with other charitable and educational institutions, became known as the “Institutions of the Empress Marie (wife of Tsar Paul I), and it was probably at this time that the symbol of the institutions was devised: a pelican nurturing her young with the flesh from her own heart. On some of the cards, in addition to the usual motto of “For the benefit of the Imperial Foundling Hospital” was the phrase “Not sparing herself she nourishes her fledgelings”.

In 1798 the Tsar granted the exclusive right to manufacture playing cards to the St. Peterburg Foundling Hospital, and for the next 20 years or so (until 1819) this right was farmed out to “tax farmers” (an example of an early standard playing card pack is here). However, the Foundling Hospital Patronage Committee decided to assume total responsibility for playing card manufacture and rely on profit margins rather than tax revenues. The intention was to build a factory under its own administration. The site chosen for the establishment of the Manufactory was in the grounds of the Alexandrovsky Manufactory, an existing textile mill founded in 1798, which was already under the aegis of the foundling hospitals. In 1817 the Imperial Playing Card Manufactory was formally opened (though card production only started in 1819). Between April-December 1819 20,000 dozen packs (240,000 packs) were produced. By 1820 this figure had increased to 115,000 dozen packs (1.38 million).

The Russian Playing Card Monopoly►

by Peter Burnett

One of the first packs produced by the Imperial Playing Card Manufactory, c. 1820 was the "Russian Tarok" or "Animal Tarok". Although the cards largely repeat well-known foreign specimens of the 18th century, it is a purely Russian product, evident from the merry peasants with little bears, wild boars, grey wolves, elephants and fabulous unicorns. Production of Russian tarok cards continued until at least 1855, when they are last mentioned in the "Table of prices of different varieties of card” of the Card Factory.

Another early pack was the Geographical pack of Russia by Konstantin Gribanov, with each card divided into four quarters, displaying the coat of arms of one of the Russian provinces, a playing card, costumes, and a list of towns. It was intended to familiarise children with the geography of the country.

In the 19th century, England was the principal exporter of playing cards to Russia and the name of De la Rue figures prominently in this connection. In October 1842 Thomas de la Rue’s younger brother, Paul Bienvenu de la Rue, travelled to St Petersburg to take charge of Russian playing card manufacture. Paul was appointed superintendent of the Russian royal playing card monopoly. The stranglehold of Tsarist despotism which prevailed at that time affected the playing-card business. In the provinces, as well as in the capital, with the early dark and the day’s work over by four o’clock, card playing was heavily indulged in. It was not unusual for gentlemen to play for eight or nine hours at a time. The Russians were the biggest playing card customers in Europe and used a million packs of cards a year. The proceeds of the Russian playing card monopoly were supposed to go towards charitable causes, but sceptical observers believed that the Tsar’s private coffers also benefitted.

A roller press was sent from London to St Petersburg and De la Rue supplied machinery, inks and paper for manufacturing the Tsar’s playing cards. The sale of these commodities meant that the Russian establishment was an important customer of De la Rue, and was the firm’s first overseas trade. His Imperial Majesty had reason to be satisfied with the results of the negotiations with De la Rue. Thomas gave such good advice and his brother Paul managed affairs so ably that by 1847 production by the Tsarist monopoly had risen to four million packs per year, making it easily the biggest playing card plant in the world. (Back in England, playing card production did not pass the million mark until 1873.)

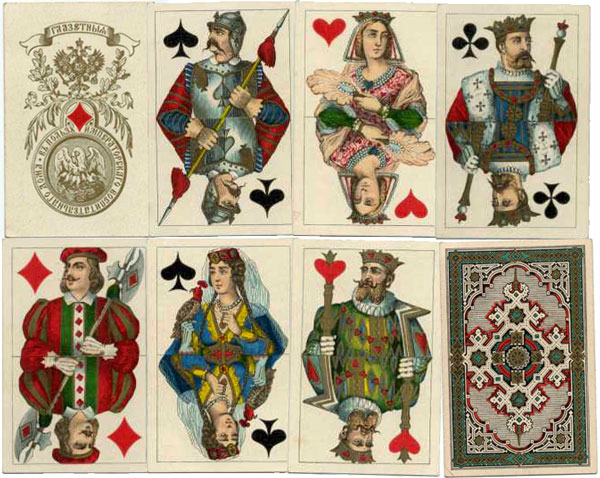

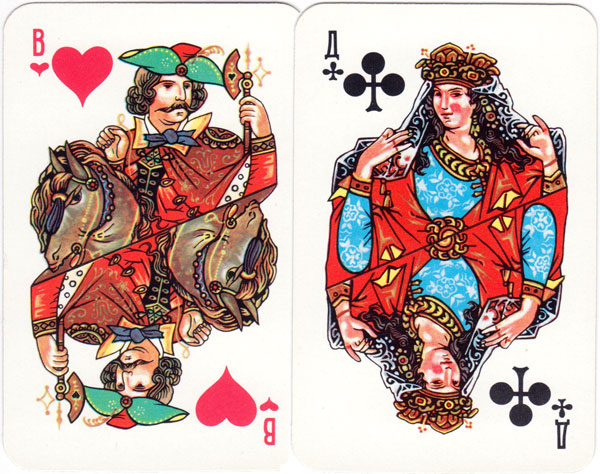

Above: cards with pseudo-medieval costumes manufactured by the Imperial Playing Card Factory, St Petersburg, c.1870. The ace of diamonds contains the stamp of the Imperial Foundling Hospital in St Petersburg to which some profits were given.

In the early 1860s the artists Mikhail Mikeshin, Adolf Charlemagne and Aleksandr Beiderman were commissioned to design new cards. Unfortunately, the negative reaction of the Tsar to these designs meant they were not produced at the time (though those by Charlemagne were eventually produced in 2018). Rokoko was produced c. 1910, and Epokha vozrozhdeniya (Age of Enlightenment) in 1875 (the latter to this day remains the most famous and popular of Russian card design).

Notable packs produced prior to WWI include “Russkii stil’ (1911) designed by a German artist working for the Dondorf factory in Frankfurt. Figures depict characters in 17th century costume – when published they were the pride of the Russian card industry. And ‘Novyi stil’ or Art Nouveau (1911) which was an attempt by the St. Petersburg Factory to renew its designs.

During the War card production was able to continue to some small degree, though production of the highest quality cards ceased completely. During the 1920s output included cards repeating pre-revolutionary designs, such as Rokoko, Russian style, Historical, and Art Nouveau.

Slavonic was produced in 1928, but the first Soviet cards with original satirical designs appeared in the 1930s; the anti-religious pack, designed by Sergei Levashev, appeared in 1934. Followed by an Anti-Fascist pack, designed by Vasilli Vlasov, in 1942. Another Anti-Fascist pack was designed in 1943 by war artist Ivan Ivanovich Kharkevich (1913-2007) but was not printed until 60 years after in 2003.

Perhaps the most famous are the cards designed by Pavel Dmitrievich Bazhenov (1904-1941) in the style of Palekh miniatures. These were designed in 1937 and exhibited at the World Exhibition of Arts and Technology, Paris 1937. In 1967, for its 150th anniversary, the Leningrad Combine of Colour Printing produced a "Jubilee" deck. Pavel Bazhenov's drawings were reworked by Eugene Pashkov. New cards have some differences from the original: a yellow frame appears at the edge of the card, and the deck has a completely new joker. The new edition contains an extra-card, indicating the anniversary edition and the authors of the deck. Today, the original sketches of the pack are stored in the Special Fund of Goznak with a diploma from the World Exhibition of Arts and Technology in Paris.

Above: “Black Palekh” for the 150th anniversary of the Leningrad/St. Petersburg playing-card factory, 1967

In 1982, Yurii Ivanov, an artist of the Leningrad Combine Colour Printing, substantially reworked Bazhenov's "Palekh" once more. They became beautiful white cards (White Palekh) with thin lacy gilding, at the same time preserving features of their prototype.

Having reverted to The Saint Petersburg Colour Printing Plant in the early 1990s, the doors finally closed in 2004. After the USSR ended and the Colour Printing Plant closed down, several local or foreign firms started to print playing cards. Today there is a thriving playing card industry throughout the country, with new companies appearing in Novosibirsk, Saratov, Stavropol as well as St. Petersburg, and attracting new artists and designers. A Playing Card Museum has been established in St Petersburg, and there is a thriving Russian Playing Card Society.

Россiйское карточное общество →

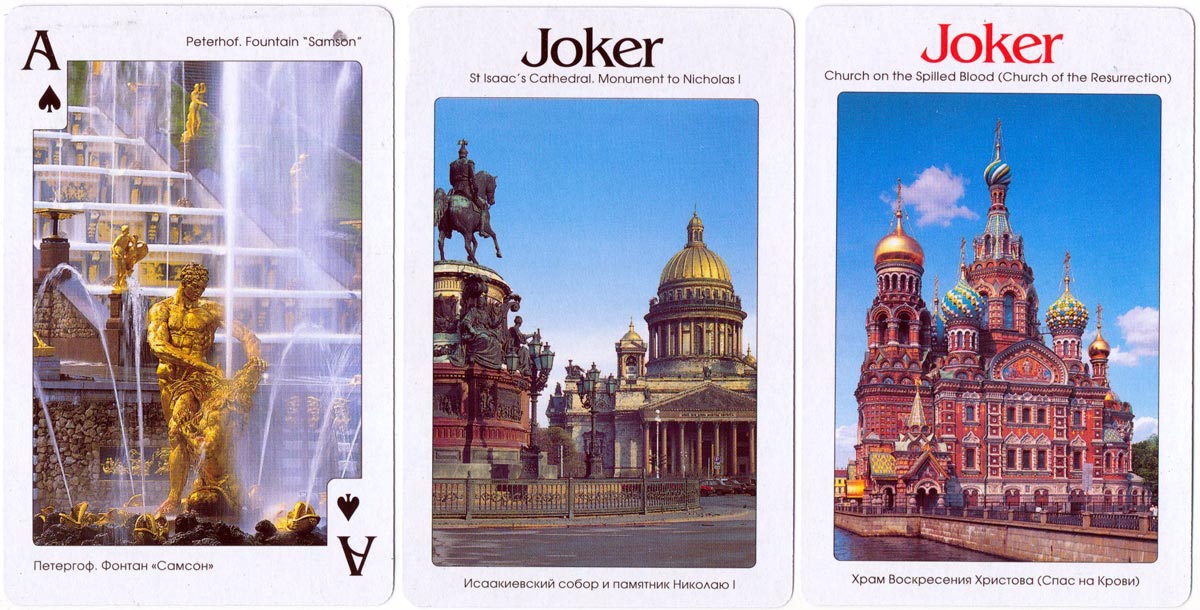

Above: St Petersburg Souvenir playing cards, 2004. See also Russia Souvenir►

Above: Russian standard pattern playing cards, c.1820

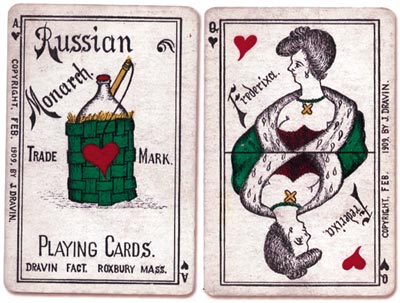

Above: Russian Monarch playing cards, 1909

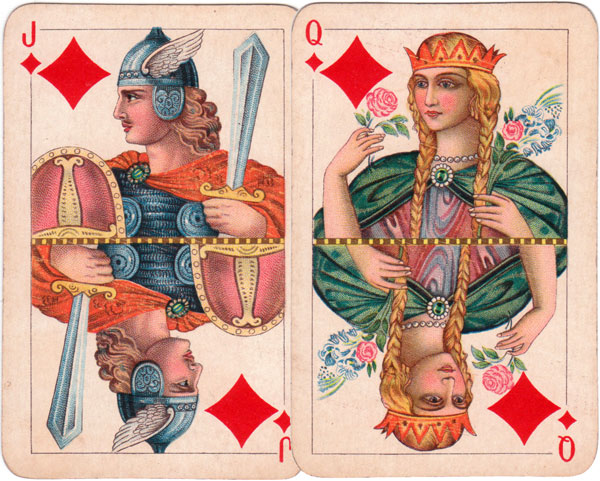

Above: Rokoko playing cards reflecting fashion of the early 18th century, 1911.

Above: “New Style” playing cards based on Literature & Theatre, 1911

Above: “Historical extra fine No.204” first published in the 1920s

Above: Four Seasons, 1971

Above: Opera themed playing cards with designs by Viktor Mihajlovich Sveshnikov, printed by the Colour Printing Plant, 1973.

Above: Maya playing cards designed by Victor M. Sveshnikov, 1975

Above: Neva playing cards designed by Victor M. Sveshnikov, 1992

Above: East Slavonic Mythology playing cards designed by Aleksey Orleansky, 1994

Above: Novosibirsk Fair playing cards designed by Sergei A. Grebennikov, 1997

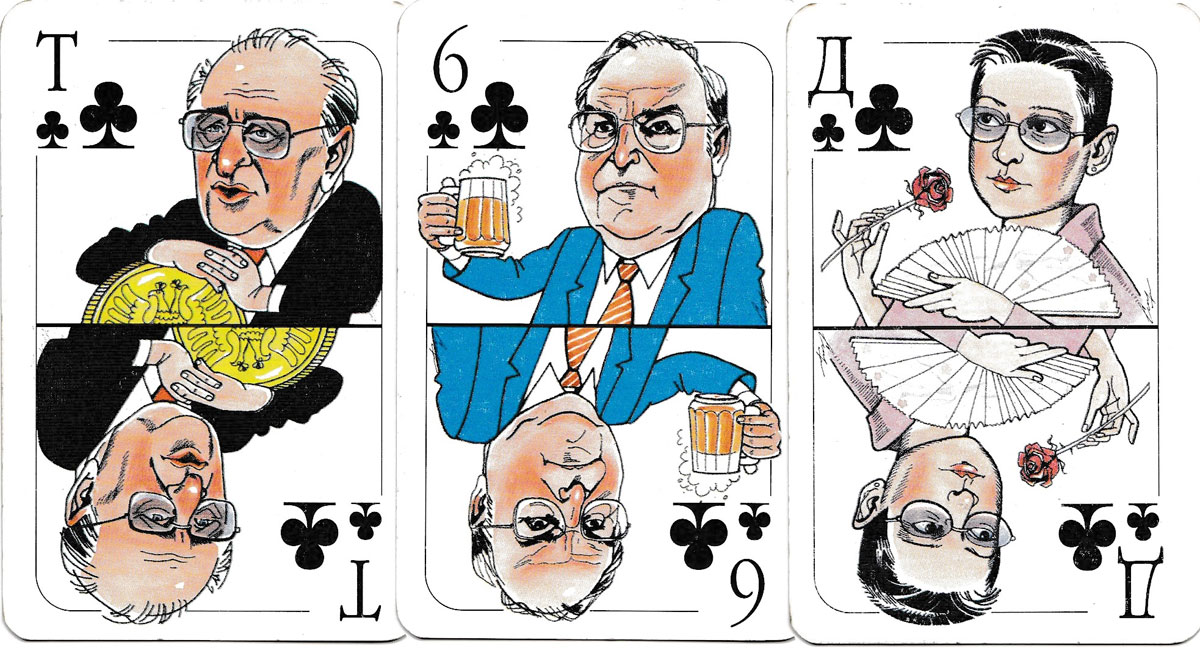

Above: Petrovskie, politicheskie karty Rossii (political cards), 1997

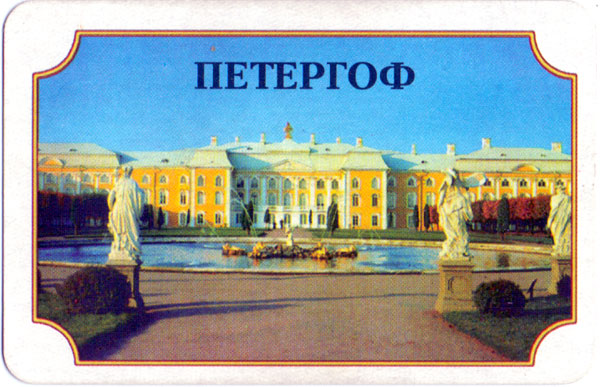

Above: “Peterhof” deck, 1999

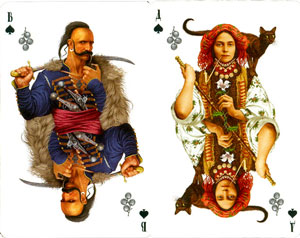

Above: “Korchma Taras Bulba” playing cards designed by Vladislav Erko, 2005

Above: “Pekelna Horugva” playing cards designed by Vladislav Erko, 2012

Above: “Trans-Siberian Express” playing cards designed by Veronika Nicolaeva, Moscow, 2015

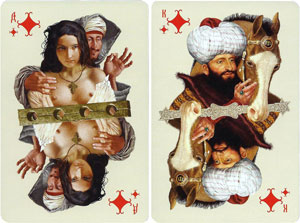

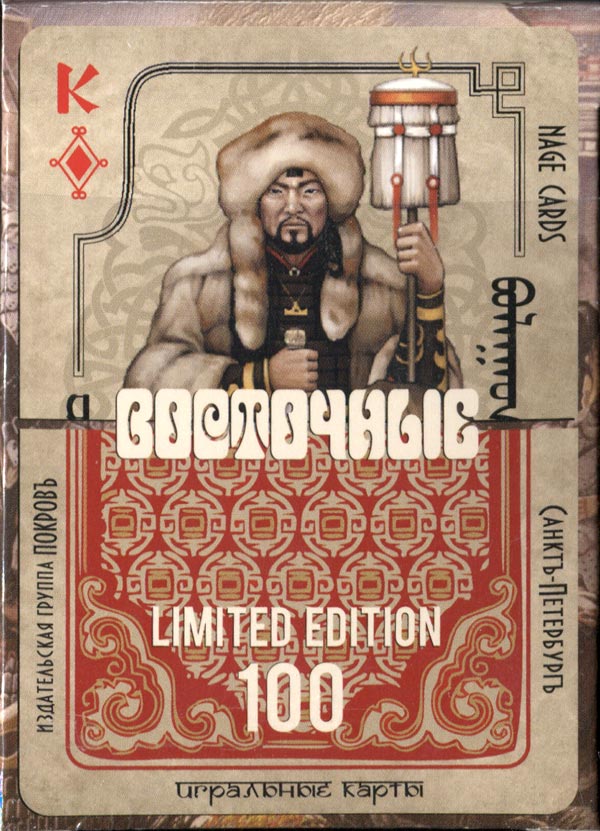

Above: “Eastern” dedicated to ethnic Buryat culture, published by the Russian Playing Card Society, 2015

Above: “Historical” playing cards designed by Nikolay Nikolaevich Karazin, 1897

Above: Russian Style, first published in 1911

Above: Slavonic cards No.501, 1928

Above: “Anti-Religions” playing cards, 1934

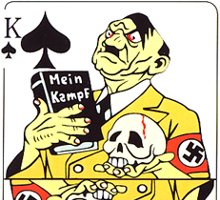

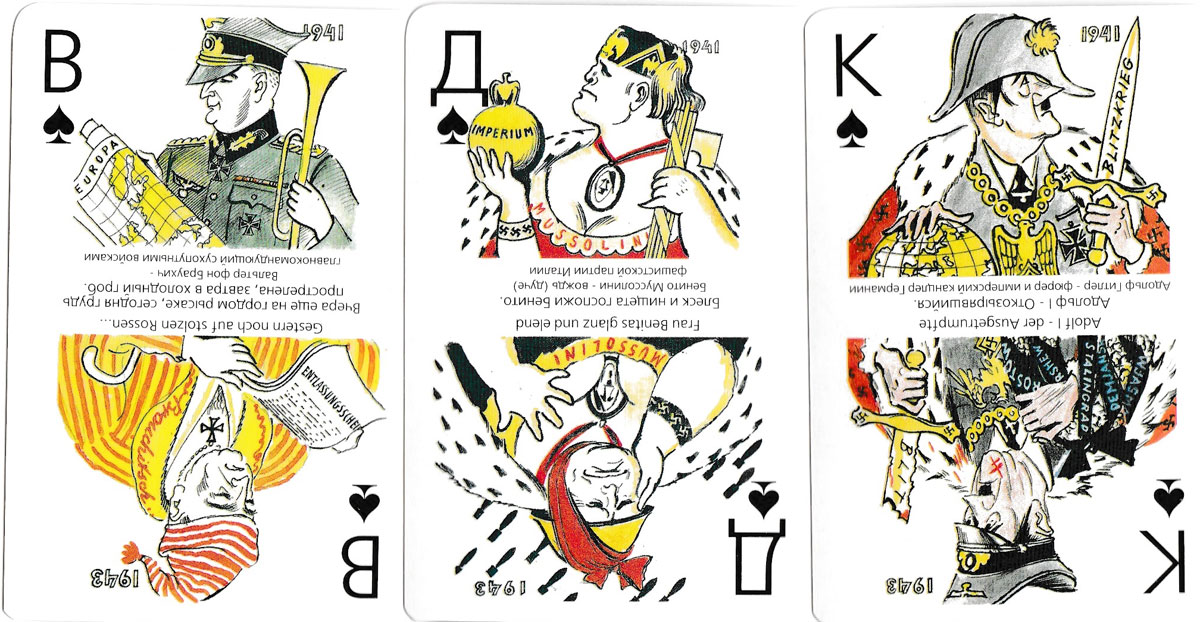

Above: Anti-Fascist propaganda pack for the Siege of Leningrad, 1942

Above: an Anti-Fascist satirical Pack, 1943

Above: SIMULTANÉ playing cards by Sonia Delaunay, 1964

Above: “White Palekh” with designs by Pavel Bazhenov, 1982.

Above: Lubok playing cards designed by Victor M. Sveshnikov, 1984

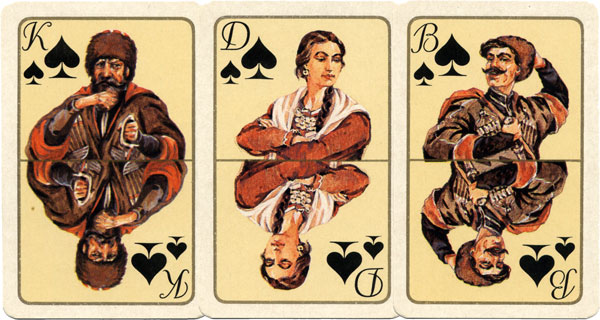

Above: Cossack playing cards designed by O. Panchenko, printed by the Colour Printing Plant, 1994

Above: “Glorious Russia” printed by Grimaud, c.1995

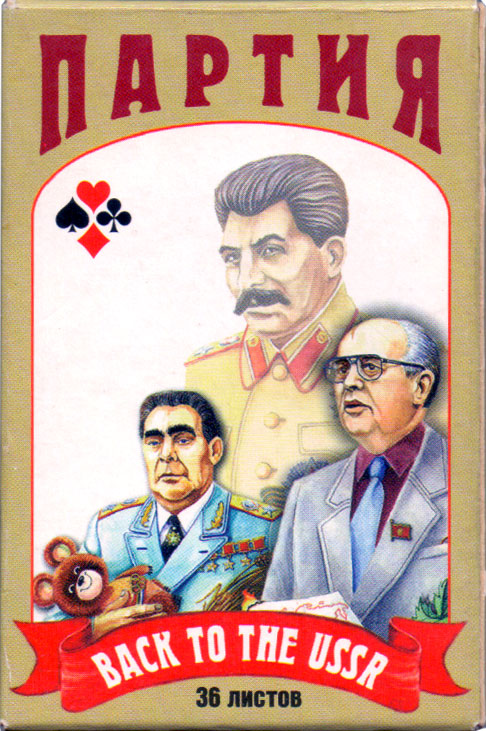

Above: “Back to the USSR” printed by Grimaud, c.1995

Above: “Palekh” with designs by Aleksey Orleansky, c.1995

![Komandirskie [Commanders]](images/countries/russia/komandirskie-0.jpg)

Above: ‘Komandirskie’ military-themed playing cards, 1997

Above: Karty Derzhavnye (Sovereign cards) with artwork by S. Zaitsev, 1997

Above: Spot the Difference playing cards published in "Razvlekatel’naia Gazetka" newspaper, 1998-1999

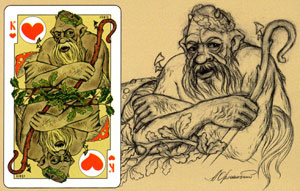

Above: “Hermits of St. Petersburg” playing cards illustrated by Alexei Bobrinsky, 2014

Above: The Four Worlds by Aleksey Zhiryakov in the style of Palekh, 2018

REFERENCES

Burnett, P.P.: “Russian playing card history: from the beginnings to 1917”, published in The Playing Card, 13 (4), May 1985, pp. 97-113 and reprinted in The Playing Card, 40 (1), Jul-Sep 2011, pp. 41-57 download here►

More Russian Playing Cards: Fortune Telling • Divination • Cosmopolitan № 2121 • Charlemagne “New Figures” •

By Peter Burnett

Member since July 27, 2022

I graduated in Russian and East European Studies from Birmingham University in 1969. It was as an undergraduate in Moscow in 1968 that I stumbled upon my first 3 packs of “unusual” playing cards which fired my curiosity and thence my life-long interest. I began researching and collecting cards in the early 1970s, since when I’ve acquired over 3,330 packs of non-standard cards, mainly from North America, UK and Western Europe, and of course from Russia and the former communist countries.

Following my retirement from the Bodleian Library in Dec. 2007 I took up a new role as Head of Library Development at the International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications (INASP) to support library development in low-income countries. This work necessitated regular training visits to many sub-Saharan African countries and also further afield, to Vietnam, Nepal and Bangladesh – all of which provided rich opportunities to further expand my playing card collection.

Since 2019 I’ve been working part-time in the Bodleian Library where I’ve been cataloguing the bequest of the late Donald Welsh, founder of the English Playing Card Society.

Related Articles

International pattern from Russia

Colourful international pattern cards from Russia sold in Latvia.

Kazakh Tales

Bold designs by K.K. Karpun and S. Nukenov inspired by Kazakh folk tales.

Egyptium

“Egyptium” is a hand-illustrated deck of fantasy playing cards with artwork by Russian artist Oleg S...

Russian Circus deck

The Russian Circus deck published by the Imperial Playing Card Factory, St Petersburg.

Wedding of Krechinsky • Свадьба Кречинского

A pack of cards depicting characters from the famous play "The Wedding of Krechinsky" by Sukhovo-Kob...

Russian folk art playing cards

Russian folk art playing cards produced by Natalia Silva, USA, 2017.

Branle playing cards

‘Branle’ playing cards inspired by a 12th-century dance, produced by Noir Arts, USA, 2015.

Theatre of Pain / Teatr Boli

Theatre of Pain / Teatr boli playing cards depicting politicians and leaders in the Caucasus territo...

CCCP playing cards

Soviet and other Communist celebrities depicted on every card, designed by Vladislav Pankevitch.

Russian criminal tattoos and playing cards

Russian criminal tattoos and playing cards, United Kingdom, 2018.

World of the New Russians

‘World of the New Russians’ (Mir novykh russkikh) satirical playing cards, 2002.

C-Arts

Collective Arts pack designed by sixty-three collaborating artists, illustrators and designers, Russ...

Ministry of Emergency Situations

Emergency response playing cards published by the Kombinat Tsvetnoi Pechati (Colour Printing Combine...

Castle Rock Club

Castle Rock Club playing cards featuring Russian rock stars and musicians, c. 2000.

Treasures of the Hermitage / Shedevry Ermitazha

‘Treasures of the Hermitage Museum’ souvenir playing cards (‘Shedevry Ermitazha’), Russia.

Trading Mart

‘Trading Mart’ playing cards published by RusJoker, St Petersburg, 2005.

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 28 days