The History of Playing Cards

Playing Cards have been around in Europe since the 1370s. Some early packs were hand painted works of art which were expensive and affordable only by the wealthy. But as demand increased cheaper methods of production were discovered so that playing cards became available for everyone...

A Concise History of Playing-cards

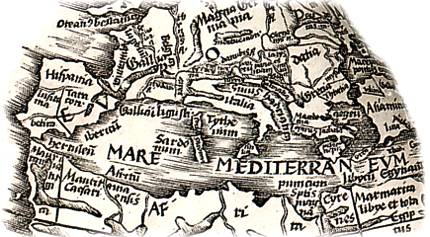

Playing Cards are believed to have originated in China and then spread to India and Persia. From Persia they are believed to have spread to Egypt during the era of Mamluk control, and from there into Europe through both the Italian and Iberian peninsulas during the second half of the 14th century. Thus, European playing cards appear to have an Islamic derivation. Some of the earliest surviving packs were hand painted works of art which were expensive and affordable only by wealthy patrons such as dukes or emperors.

But you can play card games with any old pack so as demand increased new, cheaper methods of production were discovered so that playing cards became available for everyone...

The history of playing cards in popular art is fascinating and has a long tradition. This section is an online tutorial covering the early history of playing cards. You will learn about the following topics:

Contents:

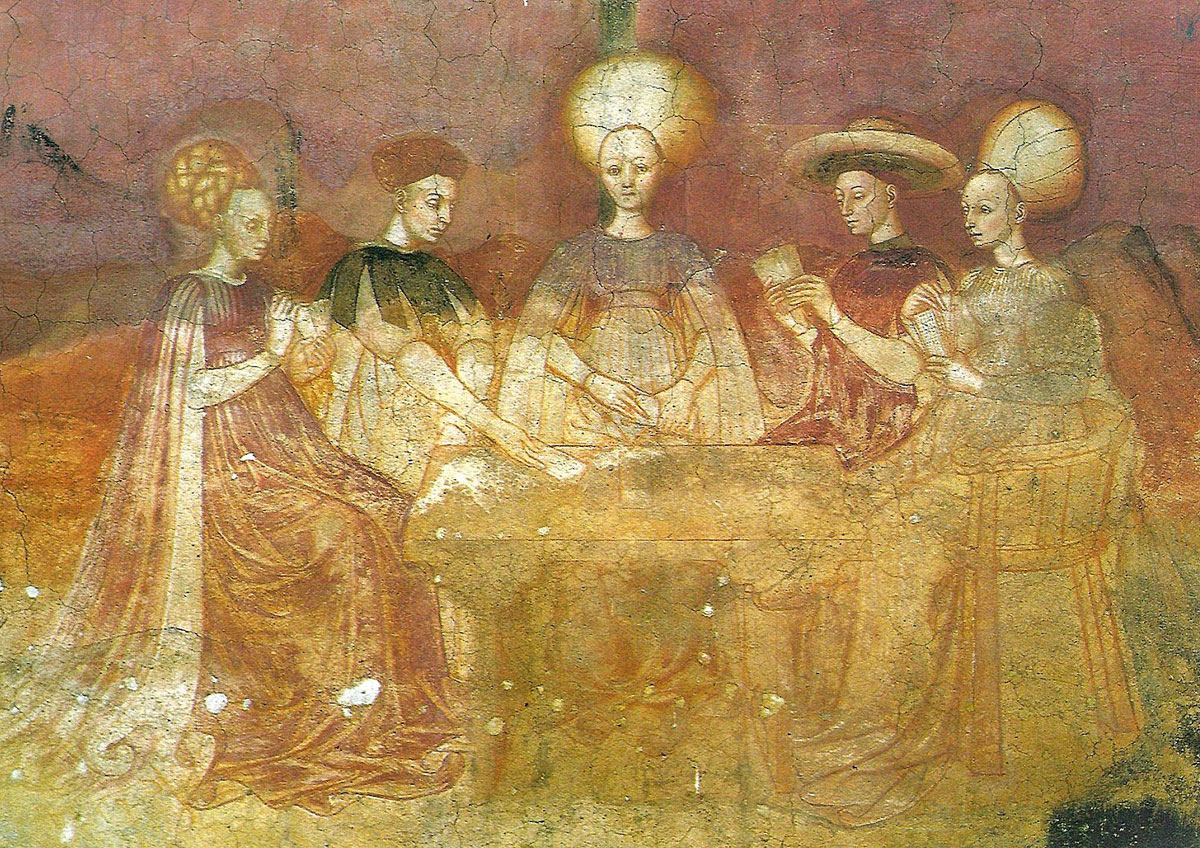

Above: British Library manuscript Add MS 12228, date 1352-1362. This is the earliest known depiction of card play, a miniature in a 14th-century manuscript of Meliadus or Guiron le Courtois (part of the romance also known as Palamedes; also known as Le Roman du Roy Meliadus de Lennoys), by Hélie de Boron. The manuscript was written with areas left blank for bas-de-page miniatures, like this one (p.313v), to be added. Hundreds were added to this manuscript, at various times and by various artists, this one probably late 14th century. The present image shows King Meliadus and his followers amusing themselves while in captivity. Players are shown holding square-cornered cards fanned in their hands, hidden from view, and playing cards onto the table. They are playing a 4-handed trick-taking game, following suit, and piling tricks cross-wise for ease of counting. The deck uses the Latin suit-signs (coins and staves are shown), and the game is being played for money or counters, shown on the table. Card playing is not mentioned in the text but there is mention of the imprisoned men entertaining themselves. Apparently the artist simply imagined the scene as involving the newly introduced and highly portable game of cards. See f.313v: British Library Add MS 12228►

Where did Playing Cards come from? The Origins of Playing Cards

A cluster of early literary references refer to the game being introduced by 'a Saracen', 'the Moorish Game' etc.

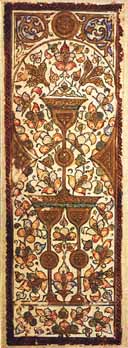

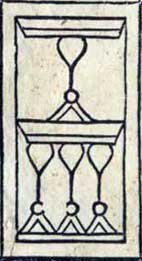

Above: Mamluk playing card, three of cups, c.1520. [Istanbul, Topkapi Seray Museum].

Above: four of cups from a set of Moorish playing cards, XV century.

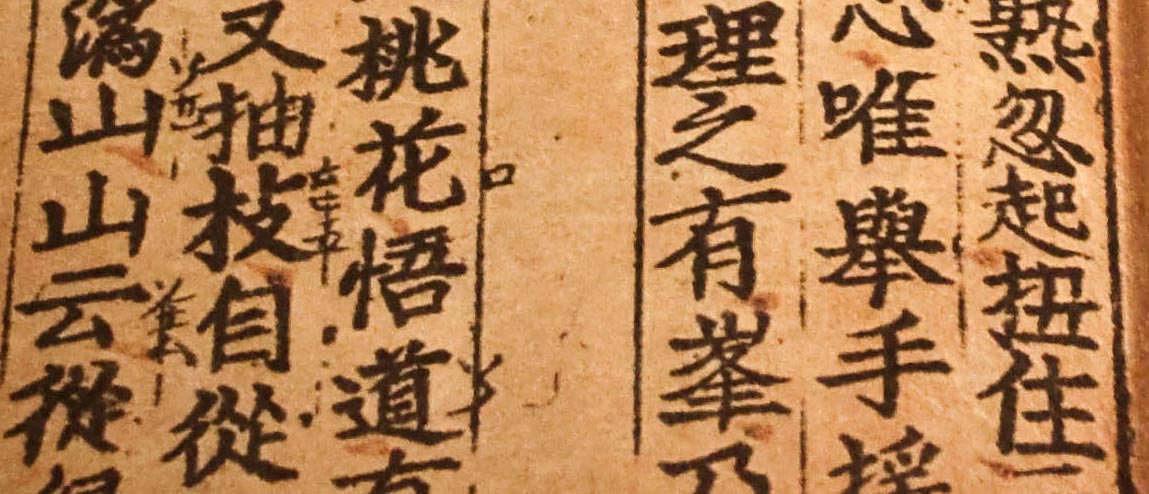

Above: Chinese playing cards.

Above: Korean printing with movable type from the Goryeo dynasty (13th century).

A cluster of early literary references refer to the game being introduced by 'a Saracen', 'the Moorish Game' etc. Etymological evidence also suggests that the Arabs introduced playing cards into Europe in the second half of the fourteenth century and that European cards evolved from the suit system and composition of these cards. These early cards were termed ‘naib’ which corresponds with the Italian ‘naipi’ and Spanish ‘naipes’, and possibly the English ‘knave’.

How were they introduced?

Scenario 1: playing cards might have been introduced into Europe by a fourteenth century traveller returning from afar, who said 'Hey chaps, guess what I saw in ….' and then proceed to manufacture a set of cards out of scraps of cardboard according to his recollections of seeing a similar game being played elsewhere. The symbols and courts might have been what he thought that he had seen, and also the game played with them.

Scenario 2: a number of travellers to Asia or Africa learned some card game, individually or as a group, and having played it with local inhabitants and perhaps each other during their travels, they decided to bring a pack or a few packs back with them, so that they could continue playing at home in Europe. When the original cards wore out they had copies made locally in Europe.

Above: ace of cups from a set of early XV century playing cards. Learn more here...

Objection: The early reference says 'introduced by a Saracen' so it seems that it was more a case of an Arabic game being introduced by a Saracen rather than some Europeans discovering it on their travels. However, any of the above may contain some truth: words shift their meanings, carry multiple meanings or outgrow their etymologies.

Look at it this way...

To make playing cards we need printing, labour and some capital.

To print the playing cards we need paper, ink and a press. Also a demand which can be satisfied and expanded so that our investment will be rewarded.

For paper to be in existence we need writing, government clerks, bureaucracy, accountancy, etc. Paper making spread throuhout Central Asia by the end of the fourth century and reached Baghdad by the eighth century. Before paper we had tablets, textiles, felt, papyrus and vellum which had already allowed these requirements to develop so that paper became a commercially feasible discovery.

All these technologies originally flourished in the far East long before they reached Europe. Printing was done with movable type in Korea several hundred years before it was ‘invented’ by Johannes Gutenberg in Europe. Before this, woodblock technology was already being used to print books, banknotes, patterns on fabrics and playing cards in China. Detailed knowledge of woodblock printing spread across the Mongol Empire from East to West Asia. Knowledge of Asian printing reached Europe, as a concept or even as a tangible artefact, and only needed to be reverse-engineered or deduced using local resources and ingenuity.

Lines of cultural inter-connection between the Far East and Europe enabled these technologies to be transmitted, to take root or materialise, when the time was right, such as when a commercial opportunity arose. In this way, playing cards reached Europe around the mid-14th century...

Download article about Early Introduction of Playing Cards into Europe

The Social Context

The Gothic age, from the 13th - 15th centuries, saw fundamental economic and religious changes. The centre of gravity shifted from the land to the towns. A new form of economy evolved, based on production for sale and exchange, in which merchants and craftsmen played increasingly important roles.

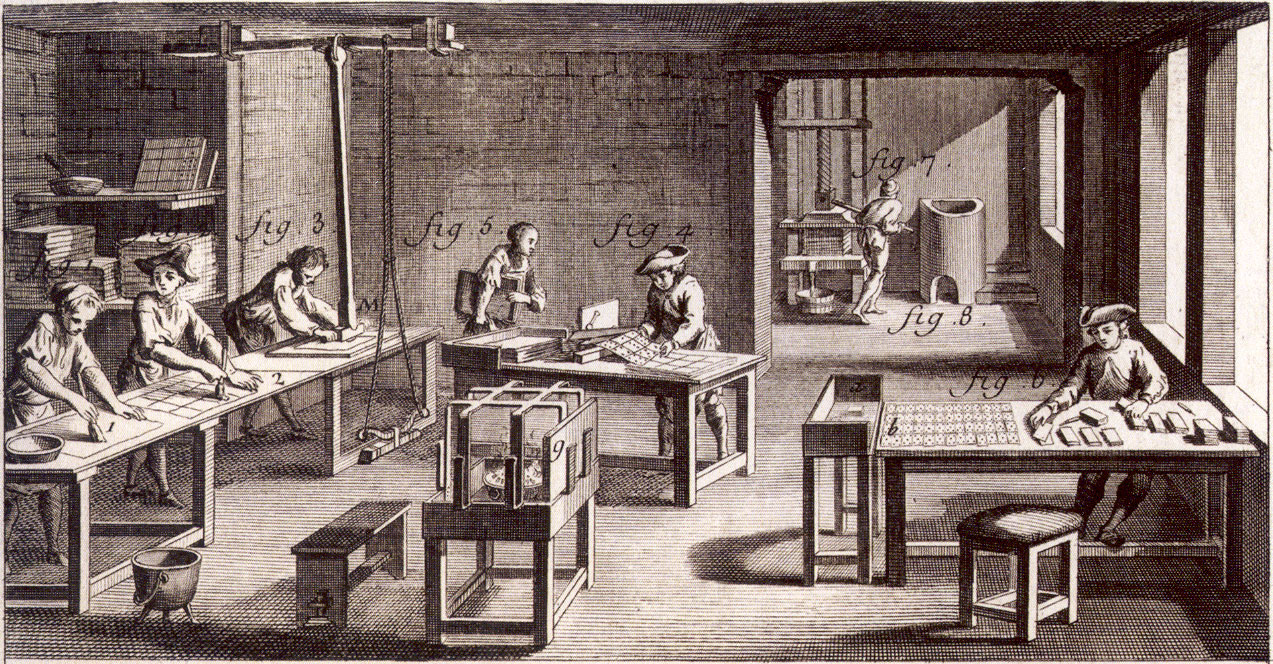

Above: The art of printing gave a great boost to the paper making industries and brought about a scarcity of old rags, until the technology for making wood pulp was improved. In the image above, we can see playing cards being pressed, polished and cut. Various utensils are lying on the floor, including a stencil, a pan and the trimmings from the edges of the cards.

How much did playing cards transfer culture? Was the transference mostly national or international?

Card games are a reflection of society. Just as cards games from, say, the Victorian era or the 1930s nostalgically evoke a tangible sense of those bygone times, cards from even earlier times, more varied in form and content, were inspired by commentaries, fables, romances, satires or burlesque scenes from daily life. In a humble way, playing cards can be seen as conduits of popular culture and taste.

The Gothic age, from the 13th - 15th centuries, saw fundamental economic and religious changes. Across the map of medieval Europe lay a tight web of trade routes, the arteries of commerce and exchange. The centre of gravity shifted from the land to the towns. A new form of economy evolved, based on production for sale and exchange, in which merchants and craftsmen played increasingly important roles. With the advance in civilisation, arts and sciences, exchange of goods and merchandise, a new breed of men had arisen who pursued money-making as an end in itself. Successful merchants displayed their wealth with extravagance and grandeur... luxury playing cards were produced for the wealthiest clients.

Many towns became centres of the arts.

Painters and makers of missals, workers in bronze, carvers of wood, sculptors, embroiderers of tapestries, goldsmiths and, later, engravers of wood and copper thrived and plied their trades.

Many of these also turned to the making of playing cards to supplement their incomes as this new industry took root.

Medieval Guilds, or Trade Unions, arose. Artisans formed groups amongst themselves to protect their interests.

Working practices were formulated and apprentices taken on.

Members tended to live in proximity, so that our street might be named "Baker Street" or "Saddler's Row".  Industry and technology were stimulated, new financial systems and new codes of international agreement were agreed, universities were established, books on all subjects were required… all favouring quicker and more affordable production.

The invention of woodcuts and then Gutenberg's invention of movable type around 1440 made possible editions of multiple copies.

Industry and technology were stimulated, new financial systems and new codes of international agreement were agreed, universities were established, books on all subjects were required… all favouring quicker and more affordable production.

The invention of woodcuts and then Gutenberg's invention of movable type around 1440 made possible editions of multiple copies.

The development of printing is the definitive symptom of the modern age: the story of the printed book is the story of one of man's greatest triumphs. Playing cards as a mass-produced commodity were greatly advanced by this development and became a part of popular culture across Europe. The art of printing made it possible for information, knowledge, ideology, propaganda and culture to be spread more effectively… it also gave a boost to the paper making industries.

Above: two versions of the Cavalier of Swords, a) French/Spanish, mid-16th century, an Arab horseman with Saracenic motifs on the shield probably alluding to Arabic presence in the Iberian peninsula, b) Japanese imitation of early Spanish/Portuguese cards carried east by Portuguese mariners.

Above: two playing cards with political motivation, a) English, 'The Knavery of the Rump', 1679, b) Argentinian, 20th century, showing Juan Domingo Perón as the King of Coins in a bid to win popular support.

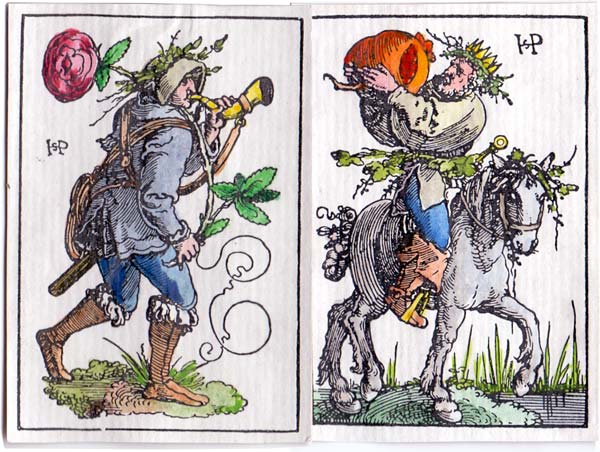

Above: two playing cards by Peter Flöttner with vulgar everyday activities of common folk satirizing bourgeois pretentiousness, Nuremberg, c.1535-1540.

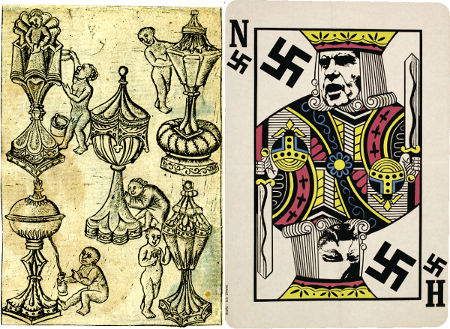

Above: a) engraved card by the Master of the Banderoles, Lower Rhine c.1470, showing ciboria (cups for holding hosts from the Christian Eucharist) adorned with naked children. Is this irreverence or playfulness, entertainingly merging spiritual and secular themes? b) political card with ideological message, 20th century.

In this way Playing cards and card playing invaded daily life, influenced society and became a part of European popular culture (or sub-culture) - even reaching as far as Japan, Latin America and North Africa. Playing cards and card players first make their appearance in chronicles and records where we learn that as soon as they arrived in Europe they were disapproved or banned by religious and secular authorities. In 1423 St Bernadin of Siena preached against games and playing cards in particular, urging sinners to repent and burn such vain things. Gradually society became more open and less bound by strict rules. By the sixteenth century a colourful lexicon of descriptive expressions and popular sayings had entered into everyday language, as well as literature, poetry and popular ballads relating to card playing, including metaphors based on cards and card games (“devil's picture book”), the moral character of gamblers (“cheats, swindlers, card-sharps”) and the divinatory, amorous, social, religious or political meaning of cards. At the same time they were a bond which united people together.

See also: Master of the Banderoles • Master PW Circular Playing Cards • Playing Cards & Religion • Design of Playing Cards • Manufacture of Cardboard • Rotxotxo Workshop, Barcelona • The Art of Stencilling.

Card Playing Enjoyed at All Levels of Society

Prohibitions of card playing and denunciations by preachers demonstrate their widespread use for gambling. It was a pastime that attracted card sharps, gamblers, cheats, swashbucklers and rogues... living by their wits. The emotional outbursts and bad behaviour upon losing were seen as immoral.

The gambler in the gaming house or tavern... unrestrained in his ardour for the game. If he wins, he continues playing; if he loses he plays again.

laying cards tend to serve two distinct purposes: gambling or the playing of games of skill. Their introduction provided a new alternative to more intellectual games such as chess and draughts, or games of luck such as dice and knuckle bones. They also provided a new way of telling fortunes or performing sleight of hand.

laying cards tend to serve two distinct purposes: gambling or the playing of games of skill. Their introduction provided a new alternative to more intellectual games such as chess and draughts, or games of luck such as dice and knuckle bones. They also provided a new way of telling fortunes or performing sleight of hand.

In many gambling games cards are used as a randomising device, like dice or a roulette wheel. The rules usually remain relatively simple: there may or may not be a banker. In games of skill the chance element is reduced. By means of devices such as bidding, capturing, collecting and melding, and more sophisticated rules, skill becomes more decisive.

Evidently both kinds of game existed in Europe since the first introduction of playing cards. Prohibitions of card playing and denunciations by preachers demonstrate their widespread use for gambling. It was a pastime that attracted card sharps, gamblers, cheats, swashbucklers and rogues... living by their wits. The emotional outbursts and bad behaviour upon losing were seen as immoral. Sir Thomas More, in his novel "Utopia" (1516) wrote that “wine tauernes, ale houses, and tipling houses, with so many noughty lewde and unlawfull games, as dice, cardes, tables tennyes, bolles, coytes” were the mothers of thieves. He preferred chess, music and good conversation.

However, instances of playing cards being used for games of skill are also recorded, as well as instances of moralising, allegory and representations of the social hierarchy…

It might not come as a surprise, in the light of the above, to learn that playing cards were also a medium for fine art. Since the late 14th century, hand-painted or illuminated, luxury playing cards were produced in artists’ workshops for wealthy clients, reflecting the elegant lives they led, and used for display or as a conversation piece, rather than for actual play. These cards were in a distinct class from the ordinary ones which were condemned or banned by the authorities, who reckoned that the greed and avarice concomitant with gambling gave rise to idleness, moral corruption or social disorder.

The case could also be made that altruism, forbearance and etiquette during play might cause good mental states to arise.

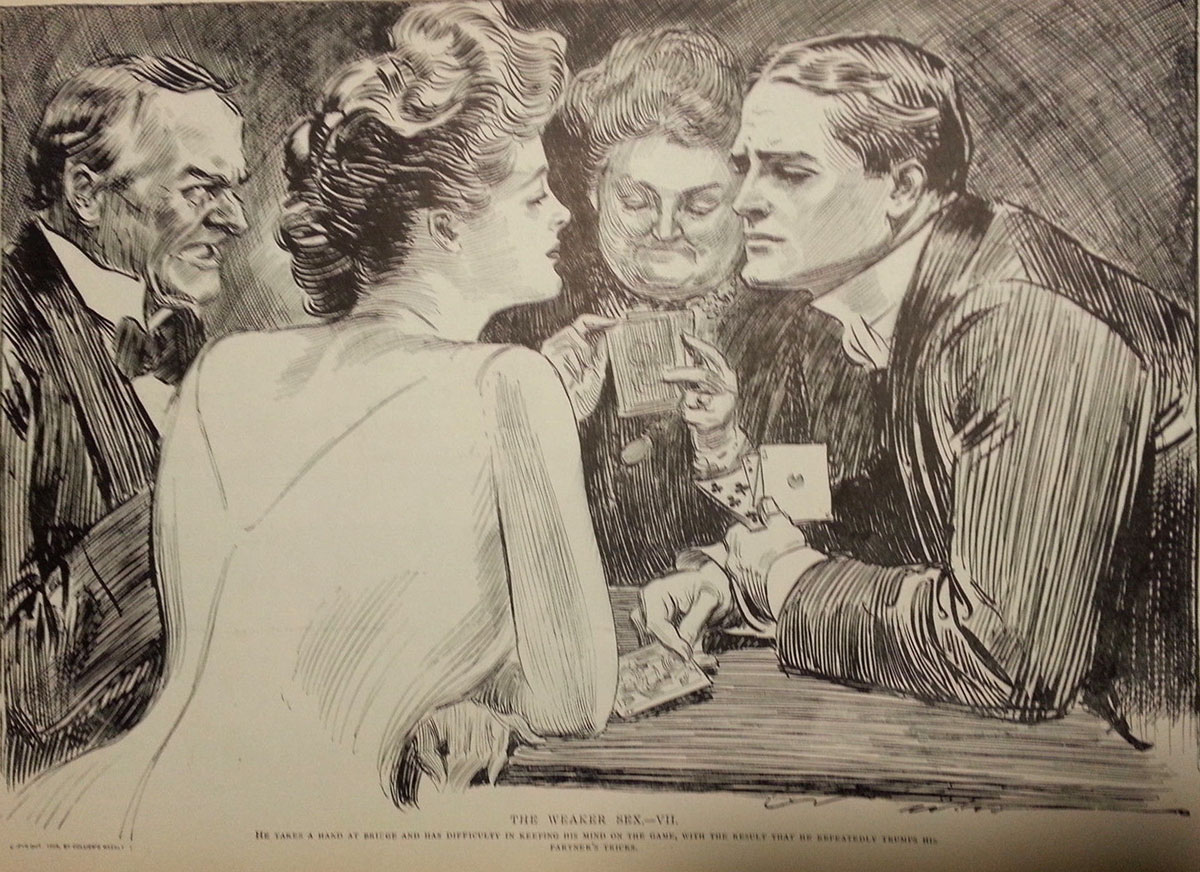

Above: he takes a hand at Bridge and has difficulties in keeping his mind on the game, with the result that he repeatedly trumps his partner's tricks.

Above: a game involving chance as well as strategy, just as in life itself...

Playing cards themselves are not necessarily the root cause of any moral decline, although the may facilitate it. The mental states and associated behaviour of the players is the real issue. Hence today we have the notion of “responsible gambling”.

See also: ‘Playing Cards and Gaming’►

What Did the Earliest European Cards Look Like?

The first European references to playing cards date from the 1370s.

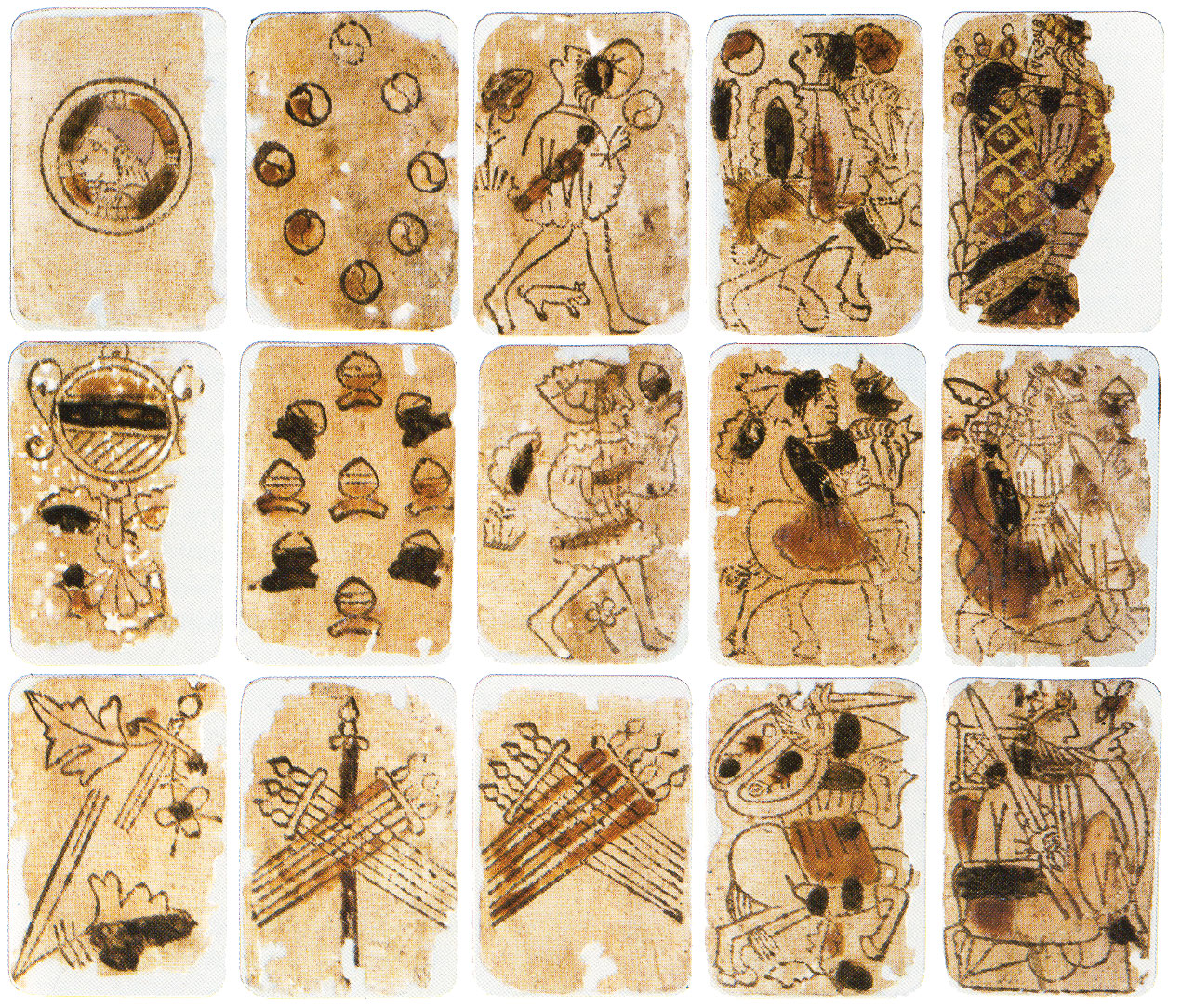

Above: XV Century Catalan playing cards, Barcelona.

Above: Master PW Circular playing cards.

Above: playing cards by the Master of the Banderoles, c.1470.

Above: Gothic Spanish-suited cards.

The first European references to playing cards date from the 1370s and come from Catalonia (Spain), Florence, France, Sienna, Viterbo (Italy), southern Germany, Switzerland and Brabant. Most of these refer to ‘a recent introduction’. No cards from this early survive, but the sources indicate that cards were being painted ‘in gold and various colours’ or ‘painted and gilded’ which suggests hand-made packs in varying degrees of quality and excellence.

The playing card pack appears to have been known, from the time of the earliest mention of it, in a fully fledged form. The suits and denominations of the earliest cards are believed to be derived from a common Mamluk, or perhaps pre-Mamluk, archetype.

Historical archives from Barcelona, 1380, mention a certain Roderic Borges, from Perpignan, and describe him as “pintor y naipero” (painter and playing card maker). He is the earliest named card-maker. Other card makers named in guild records include Jaume Estalós (1420), Antoni Borges (1438), Bernat Soler (1443) and Joan Brunet (1443). Cards were being produced by craftsmen or artists, printed from woodcuts, engraved, ‘painted or gilded’.

The earliest surviving cards are from the fifteenth century, and most of these were made on pasteboard manufactured from 3, 4 or up to 6 sheets of paper glued together. Cards were often much larger sizes than today, and the images were either hand drawn or printed from woodblocks or printed from copper engravings. In the early days, the attention of the makers was the design of the faces, while the backs were plain. The colouring was often done using stencils. Suit systems varied greatly and a wide range of everyday objects were depicted as suit symbols... boars, bears, flowers, falcons, hounds, lions, clubs, cups, ciboria, hares...

The Medieval mind delighted in the ornate and colourful, and the art of the miniature was much admired and practised. Occasionally the playing card becomes the focus of excellent miniature design and artistry.

How Did They Evolve? Cultural Diversity & Localisation.

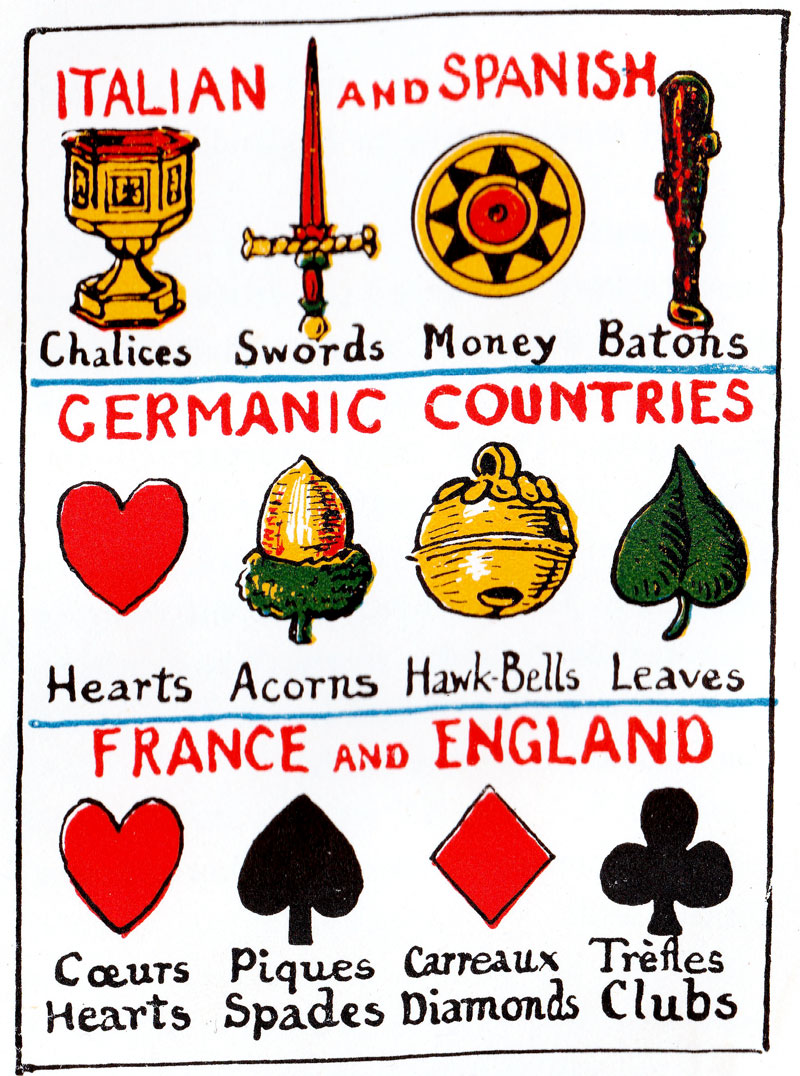

Above: different suit symbols from different parts of the world.

The idea of suit symbols may have originated with Chinese 'Money' cards. Why did countries change suits, decks, card size, and games as they adopted playing cards into their own culture?

The idea of suit symbols may have originated with Chinese ‘Money’ cards. However, the suits that made their way into Europe were probably an adaptation of the Islamic cups, swords, coins, and polo sticks. As Europeans didn't understand what the polo sticks were they reassigned them as batons and they became what we know today as the ‘Latin’ suit-signs. These were used in Spain and the Iberian peninsula and Italy until French card makers had a brilliant commercial coup of inventing the ‘French’ suit-signs which are much simpler to reproduce.

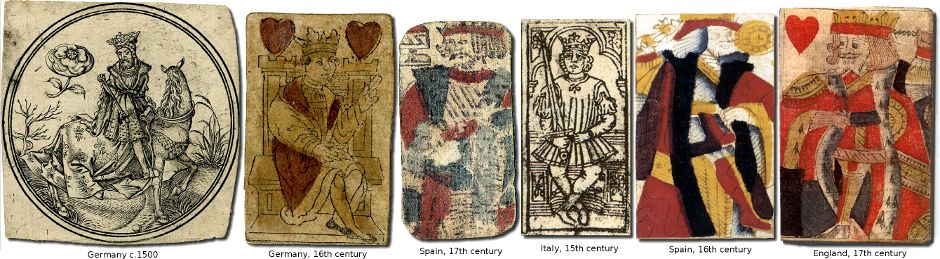

Meanwhile, by the end of the fifteenth century, playing cards had spread over most of Western Europe. The diverse cultural contexts and printing techniques led to a diversity of playing card types and styles. Stereotyped designs peculiar to particular regions evolved and became standard patterns. But the combinations of court hierarchy and suit symbols were not always stable or uniform. In some cases we see Kings mounted on horseback, in other cases seated on thrones. Some packs contained Queens and attendants, others preferred horsemen and foot soldiers. Some packs had additional trump cards or five suits. In some regions the suit signs were somewhat fluid and included everyday objects, animals, helmets, hunting equipment or flowers. Packs are known with suit symbols such as: roses, crowns, pennies and rings or bells, hearts, leaves and acorns.

Above: different local interpretations of the generic idea of a 'King' in playing cards.

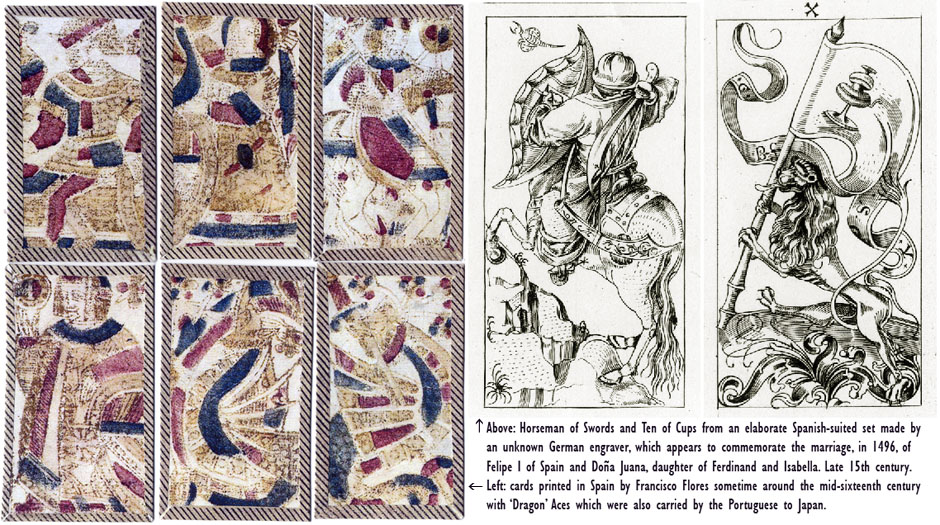

We do not know precisely why this happened, but we can speculate that different cultural, artistic and iconographic traditions, contrasting feudal, aristocratic or imperial court hierarchies, conservative or liberal tendencies, the migration of craftsmen as well as the exportation of artisanal goods and crafts to other markets, even linguistic influences and fashions in clothing, all played a part in how the pack of playing cards evolved and was adopted in different regions. For example, 16th century Portuguese mariners introduced their latin-suited 'Dragon' playing cards into Japan. They were subsequently banned in a prohibition of 1648 but they re-appeared in disguised, hybrid forms and evolved into several variant types (see example). The dragon on the Aces was adapted by the Japanese in Unsun karuta, and by the Javanese as well, whilst the name for the cards, “karuta”, is derived from the Portuguese. Similarly, the native American Indians made cards with their own interpretation of Spanish suit symbols based on those used by Spanish sailors and kept them even after French-suited cards had arrived from Europe.

As a third and final example, it is known from several sources that cards were exported at an early date from Germany to Italy, packed in barrels. Late 15th century German cardmakers produced Italian and Spanish-suited cards in the new technique of engraving, in an elaborate Gothic style, which were exported to foreign markets and influenced local production in those places.

To summarise, first came the Latin (Spanish) suit systems, which are still employed in Spain and the Americas, Italy, the Philippines, some parts of France and North Africa. The courts were probably all-male to begin with, but female pages and queens were soon introduced. Germanic suit systems (including Swiss) evolved after a period of experimentation with different combinations of suits, and finally the French suit system was invented as a technical innovation in which the numeral cards were simplified, and which has become the most widely-used suit system around the world.

Methods of Production The Earliest Playing Cards

Luxury hand-painted packs were only available to a few, who enjoyed them privately or with select company. The printed or mechanically-produced versions, cruder in design and execution, were viewed simultaneously by larger audiences but were prone to deteriorate more rapidly.

Increase in demand for cultural objects led to the inventing of quicker and cheaper production methods… woodcuts, movable type, paper instead of parchment, multiple copies. As card-playing became more popular production was accelerated by these alternative processes, including hand-made cards, cards printed from woodblocks or using stencils, or other improvised techniques.

Below Left: archaic sixteenth century Spanish playing card by Francisco Flores. Right: XV century printed German playing card / XV century hand-painted hunting pack.

Early packs involved artisan methods of card production which was time-consuming but the resulting cards were very sturdy. Pasteboard was manufactured from several sheets of paper glued together. More expensive cards were produced from engravings in copper using the skills of the goldsmith and engraver and illuminated with many colours including gold and silver. These cards have greater detail and a more naturalistic use of line. Such packs were given as wedding gifts, bequeathed as heirlooms and regarded as valuable items. They were often produced for collectors or as curios for princely display cabinets.

Luxury hand-painted packs were only available to a few, who enjoyed them privately or with elite company as objects of fashionable esteem. The printed or mechanically-produced versions, cruder in design and execution, were viewed simultaneously by larger audiences but were prone to deteriorate more rapidly especially if they were heavily used. Wood engraving and traditional woodcuts, despite the modern developments of chemical, mechanical or electronic processes, still remain the most expressive forms of illustration, adding a sense of vibrancy, old world chivalry and romance.

See also Francisco Flores, The South German Engraver, Mantegna Tarocchi, Rotxotxo Workshop Inventories, Barcelona Amos Whitney Playing Card Workshop.

Above: illustration of Card Maker's Workshop from L'Encyclopedie by Diderot, d'Alembert, Paris, 1751. At the left-hand side we can see pasting operations and polishing by means of flints fixed to apparatus suspended from the ceiling. In the back room freshly pasted sheets are being pressed and the excess water squeezed out into the bucket. In the central area, sheets of cards are being cut using a cutting machine whilst at the right-hand side finished cards are being inspected and sorted into complete packs. Learn more →

See also: Amos Whitney's Factory Inventory Chromolithography Design of Playing Cards Make your own Playing Cards 17th Century Replica Pack Woodblock & Stencil Playing Cards Letterpress Printing Manufacture of Cardboard Manufacture of Playing Cards, 1825 Rotxotxo Workshop Inventories, Barcelona The Art of Stencilling.

Sources of Imagery

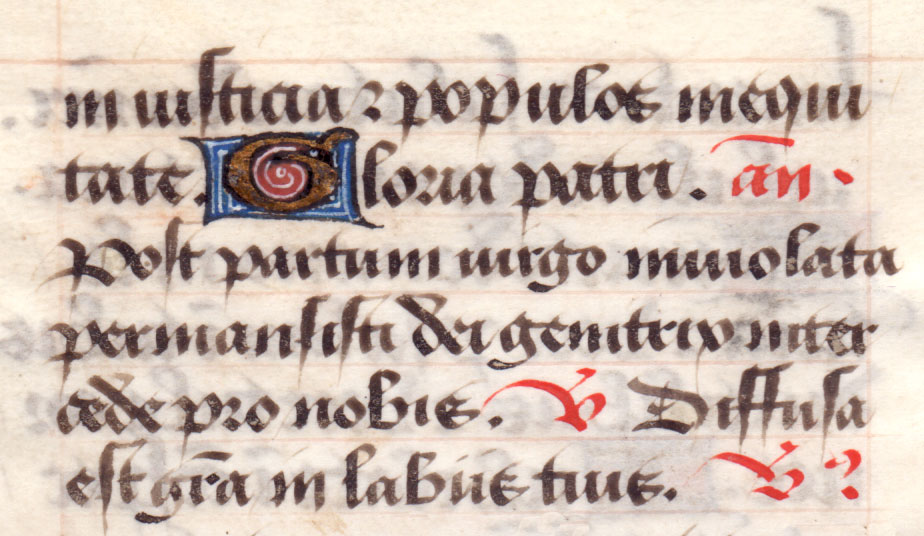

Imagery on many early playing cards resembles the stock repertory of animals, plants, birds and flowers which recurs almost identically in the marginal drollery, miniature illustrations and trompe l'oeil of widely divergent manuscripts, and in sculpture."

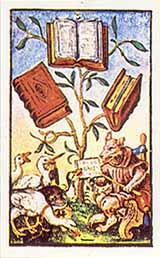

Above: playing cards were often featured in moralistic or satirical allegories, showing how they were rapidly absorbed into the popular imagination.

The repertoire of motifs employed in playing cards had long been in development in other applied crafts. The craftsmen's tradition throughout the medieval period was to work from sketch-book models, collected on scraps of vellum. These models were copied time after time, so that images spread between workshops and from master to pupil. Images acquired during journeys abroad often contained errors of observation and proportion which were compounded by subsequent copying.

The repertoire of motifs employed in playing cards had long been in development in other applied crafts. The craftsmen's tradition throughout the medieval period was to work from sketch-book models, collected on scraps of vellum. These models were copied time after time, so that images spread between workshops and from master to pupil. Images acquired during journeys abroad often contained errors of observation and proportion which were compounded by subsequent copying.

Whilst the main court card hierarchy was inspired by the social structure at court, and early suit systems were often associated with the hunt, much secondary imagery on early playing cards resembles the figures which recur in the borders and marginal drollery, miniature illustrations and trompe l'oeil of illuminated manuscripts or in tapestry, carving or sculpture. Often the theme was a playful allusion to tournaments, cavorting children or mock warfare between animals, frequently surrounded by fruits, flowers, acanthus leaves, birds, monkeys and grotesques. Cards were produced by artisans whose main source of income might not necessarily have been playing cards. Abilities varied: where lesser artists represented the stock subjects in a stereotyped way, others were able to visualise scenes afresh.

Designs would also have been influenced by written texts, books on hunting, mystery plays and moralised stories. Plants from the herbal, beasts from the bestiary, birds and insects from the Books of Hours, all suggesting a symbolism, a semiotic language, echoed the everyday world of popular beliefs and folklore.

Above: Lion motif on XIV century choir stall; 9 of lions and 3 of herons engraved by the Master of the Playing Cards, c.1450-60. 137 x 91 mm. The central lion has also been identified as an illustration in the 42-line Bible of Mainz printed by Gutenberg, around 1454/55. Herons occur in the borders of a number of manuscripts and early printed books. See also: South German Spanish-suited engraved playing cards • Master PW Circular Playing Cards.

Thus, the pack of playing cards gained a format and structure of its own, and became a new language. In the earliest packs the suit symbols might be everyday objects (which may or may not have had any symbolic meaning): flowers, animals, birds, shields, crowns, pennies, rings, pomegranates… spades, hearts, clubs and diamonds were invented later.

Many early examples of playing cards were preserved inside the covers of old books, where they were used as stiffener. This is fortunate, because nearly all the others have perished.

See also: Master of the Banderoles • Design of Playing Cards • Make your own Playing Cards • Master PW Circular Playing Cards

The Renaissance

With the onset of the Renaissance in Italy, the new spirit of Humanism was spreading through Europe bringing a change of form and direction. The design of playing cards reflected these changes, in their style and thematic content.

With the onset of the Renaissance in Italy, the new spirit of Humanism was spreading through Europe bringing a change of form and direction. The Middle Ages had given birth to the dawn of the modern era. The style and thematic content of playing cards reflected the new world view. This new influence did not reach certain parts of Europe until the high and late Renaissance in the 16th century. Following in the wake of Italian art, the German Renaissance developed a new form of medieval knightly culture. Imaginative decks of playing cards were produced by Jost Amman, Schäufelein, Schön and Peter Flötner.

Artists were commissioned to paint anything from wall frescoes through Books of Hours to illuminated playing cards, thereby exhibiting the taste and cultivation of the patron. In some cases the imagery had a moral, Christian, instructional or philosophical content, whilst in other cases it was based upon popular culture, often satirical or else merely conventional or adorned with the owner's heraldic devices.

Left: Visconti tarocchi playing card, Milan, Italy, c.1445. Click here to see more.

See also: Mantegna Tarocchi - Peter Flötner - Guildhall Library Tarot cards. Download article about Origins of Imagery in the Tarot.

REFERENCES

Pratesi, Franco: on the history of playing cards and card games, Online here►

Christensen, Thomas: “Gutenberg and the Koreans: Did East Asian Printing Traditions Influence the European Renaissance?” in "River of Ink: literature, history and art", Counterpoint, Berkeley, Ca, 2014.

Chamorro Fernández, María Inés: Léxico del naipe del Siglo de Oro, Ediciones Trea, S.L., Gijón, 2005.

Hoffmann, Detlef: The Playing Card, an illustrated history, Edition Leipzig, 1973

Mann, Sylvia: All Cards on the Table, Jonas Verlag/Deutsches Spielkarten-Museum, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, 1990

Hoffmann, Detlef: The Playing Card, an illustrated history, Edition Leipzig, 1973

By Simon Wintle

Member since February 01, 1996

I am the founder of The World of Playing Cards (est. 1996), a website dedicated to the history, artistry and cultural significance of playing cards and tarot. Over the years I have researched various areas of the subject, acquired and traded collections and contributed as a committee member of the IPCS and graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal. Having lived in Chile, England, Wales, and now Spain, these experiences have shaped my work and passion for playing cards. Amongst my achievements is producing a limited-edition replica of a 17th-century English pack using woodblocks and stencils—a labour of love. Today, the World of Playing Cards is a global collaborative project, with my son Adam serving as the technical driving force behind its development. His innovative efforts have helped shape the site into the thriving hub it is today. You are warmly invited to become a contributor and share your enthusiasm.

Related Articles

Patience by Joseph Glanz

A refined and distinctly European Patience pack by Joseph Glanz from Austria.

Modern Swiss-German Pattern (carta.media)

Modernizing tradition: balancing clarity and continuity in regional card design.

Tactics Design

Late modernist Japanese playing cards designed by Masayoshi Nakajo for Tactics Design.

Tarot Beirut

A beautiful Arabic Tarot : a mystical tool for positive guidance and well-being.

The Decadent Deck

Studies in the eroticism of the female body by Inge Clayton.

Historic Shakespeare

“Historic Shakespeare” playing cards featuring Shakespearean characters by Chas Goodall & Son.

Sunday Night / Nichiyoubi no Yoru

An irreverent, avant-garde deck unofficially titled "Nichiyoubi no Yoru" (Sunday Night), designed by...

Copechat Paramount Sorting System

Preserving the past: a specimen deck showcasing edge-notched cards and their ingenious sorting syste...

Emilio Tadini playing cards

Beautiful dreamlike playing card designs by Emilio Tadini.

Jeu Révolutionnaire

Court cards and aces from a French Revolutionary pack by Pinaut, Paris, c.1794.

French Revolutionary cards by Pinaut

Seven cards from a French Revolutionary pack by Pinaut featuring characters from classical antiquity...

Zürcher Festspiel 1903

Swiss-suited pack designed by Robert Hardmeyer featuring figures from art and politics.

Tarot de las Coscojas

Historical playing card design, tarot symbolism and an almost psychedelic medieval surrealism.

Never Mind the Belote

Limited edition Belote pack with designs by a collective of 24 street artists.

Playing card designs by Franz Exler

Reconstruction of playing cards from the original 1903 designs.

MITSCHKAtzen

Clever cat designs by the Austrian artist and illustrator Willi Mitschka.

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 28 days