Secondary Uses of Playing Cards

The unprinted backs of playing cards have led people to use them for secondary purposes such as memorandum slips, bibliographic index cards, for declarations of love, rendezvous notes, emergency money, visiting cards and so on.

Is a Pack Only for Playing Games?

The format of the pack - suit symbols, numeral cards, court hierarchy - has served many secondary purposes beyond a gaming device.

It is debatable whether some early packs of cards were actually intended for play at all. Some were made just to look at, admire and study; see example → or even for the self-indulgent, narcissistic enjoyment of the super-rich who could afford illuminated cards adorned with gold. They were more than just a plaything, people could read the symbols and inscriptions, draw analogies or see meaning.

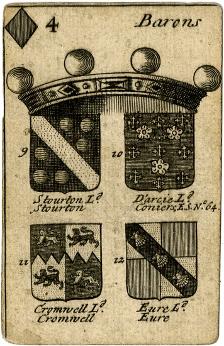

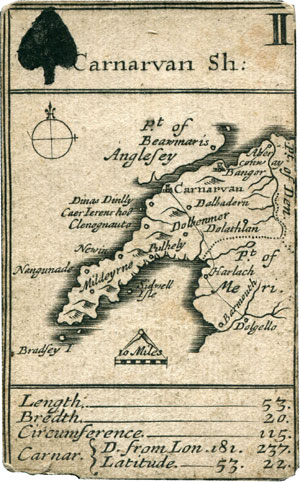

Man's mind likes to categorise and classify experience… the elements, cardinal points, lunar cycles, virtues, heavenly spheres, temperaments, taxonomies and hierarchies. Playing cards are convenient to use as a practical 'mnemonic' or device for representing life's basic facts, a memory aid or teaching tool, a means of condensing knowledge. The subject can be anything from botany to heraldry, from cosmology to geography. For instance, a set of educational cards was invented in 1507 by Thomas Murner, a Franciscan monk. Political satire has also been an inspiration for playing cards.

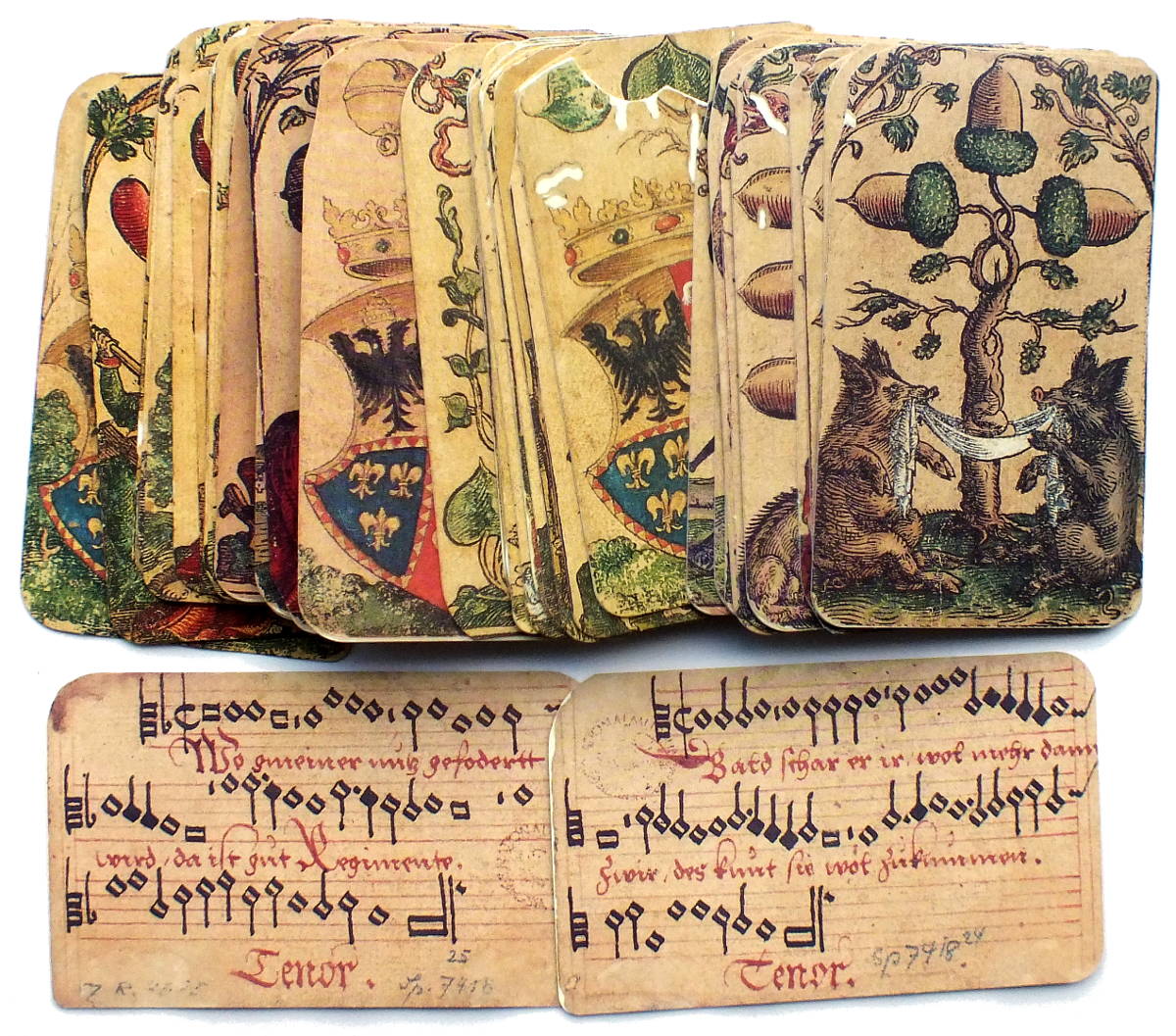

Above: cards from a satirical pack designed by Peter Flöttner of Nuremberg, c.1545. The backs of the cards contain the vocal scores for German songs. Cards from the facsimile edition published by Ferd Piatnik & Söhne, Vienna, 1993.

The format of the pack - suit symbols, numeral cards, court hierarchy - has served many secondary purposes beyond a gaming device. It can be used for predicting the future, teaching heraldry, as a pocket map, and in the case of the tarot, it has almost become a popular religion. This is also the origin of quartet and Happy Families games which have educational benefits.

Until the latter end of the 18th century playing card backs were left plain white. The problem with this was that card backs became easily marked during play, and would thereby become recognisable by an opponent. It was expensive to buy another new pack, so spoilt cards would be returned to the workshop for cleaning. Some playing card manufacturers began to print repeating geometric patterns of stars or dots on the reverse of the cards to minimise this problem, but until then the white backs of playing cards were often used for secondary purposes, from currency to visiting cards to library classification cards...

Until the latter end of the 18th century playing card backs were left plain white. The problem with this was that card backs became easily marked during play, and would thereby become recognisable by an opponent. It was expensive to buy another new pack, so spoilt cards would be returned to the workshop for cleaning. Some playing card manufacturers began to print repeating geometric patterns of stars or dots on the reverse of the cards to minimise this problem, but until then the white backs of playing cards were often used for secondary purposes, from currency to visiting cards to library classification cards...

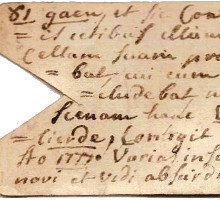

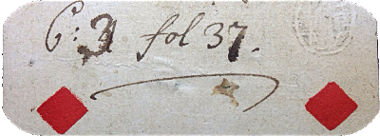

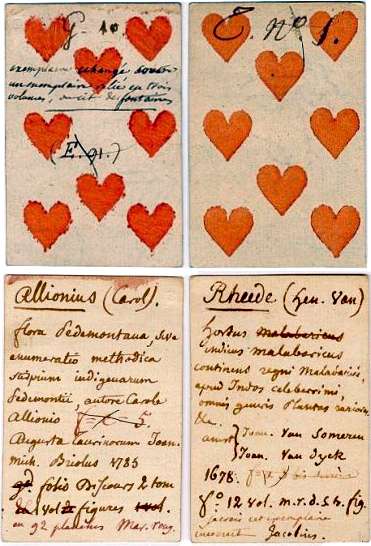

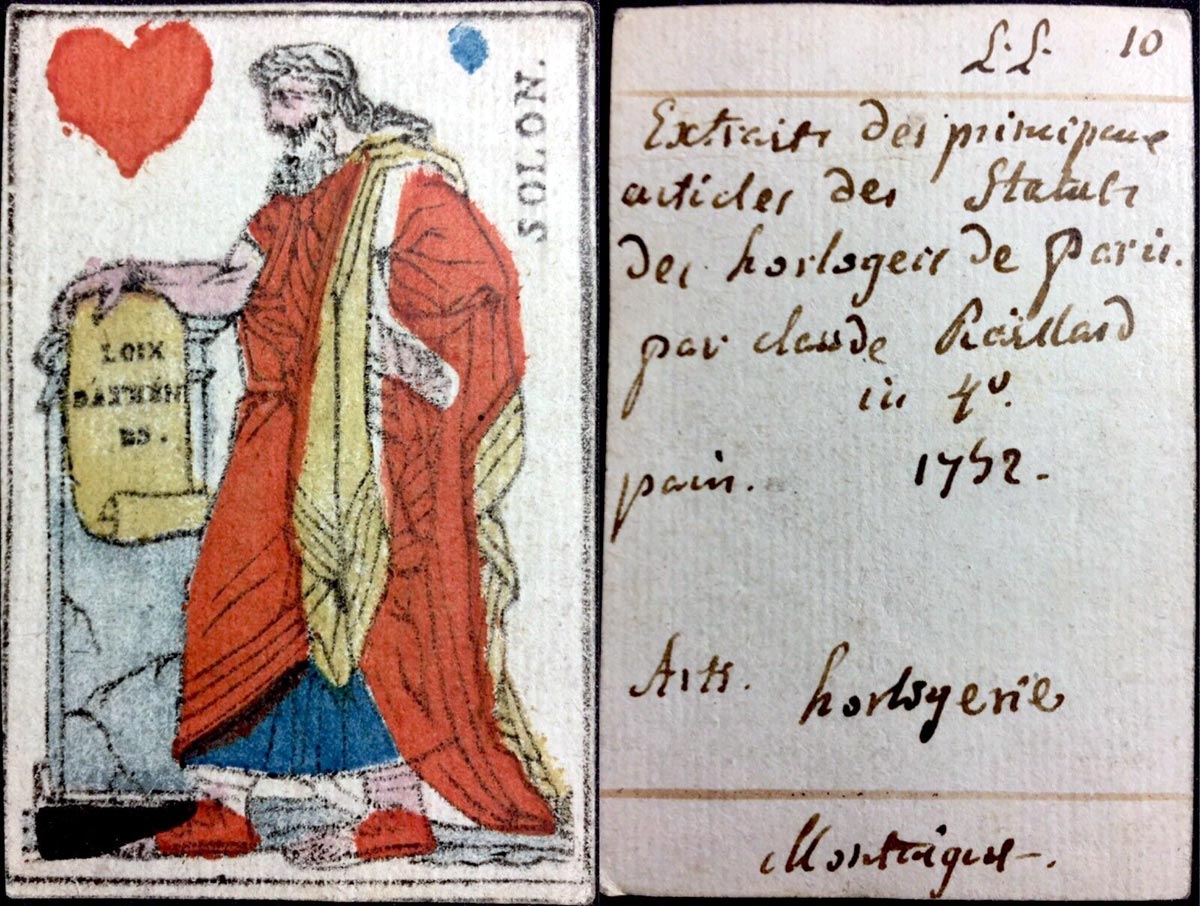

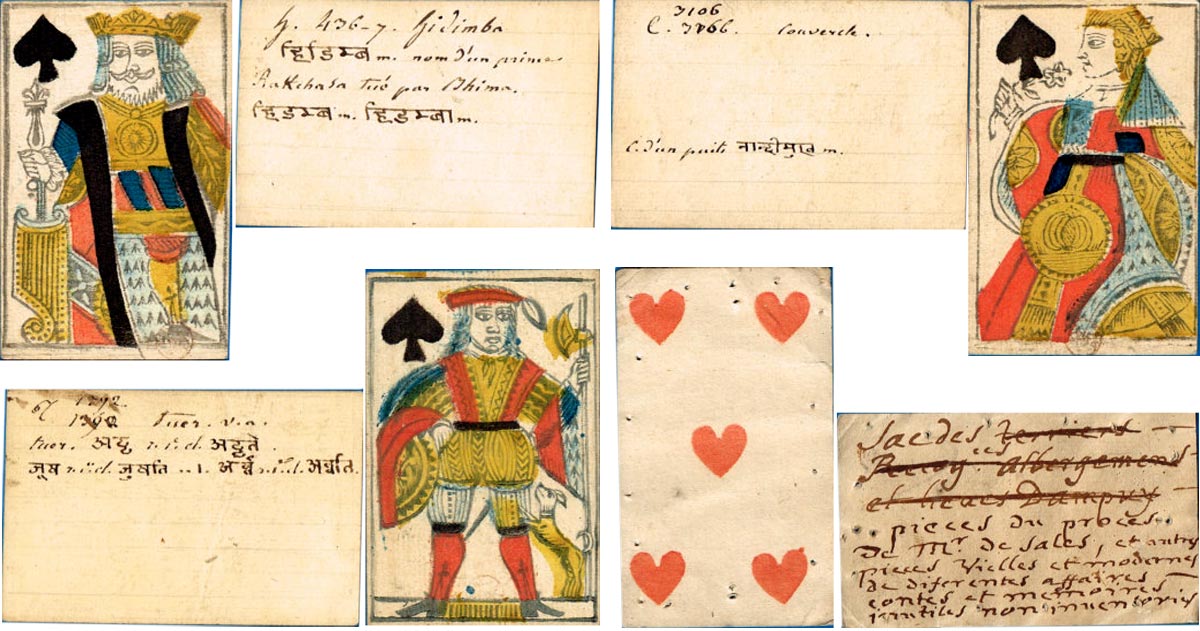

Above: repurposed playing cards with handwritten notes on the reverse.

Since their first appearance as printed artefacts, surplus or defective proof sheets of playing cards were re-used as stiffening material inside book covers. Some of the earliest playing cards have survived in this manner, having been discovered when the book cover needed repair. Sixteenth century miniatures were usually painted in body colour on playing cards or on vellum. More recently, the unprinted backs of playing cards have led people to use them for secondary purposes such as memorandum slips, bibliographic index cards, for declarations of love, rendezvous notes, credit notes, pass slips or emergency money►

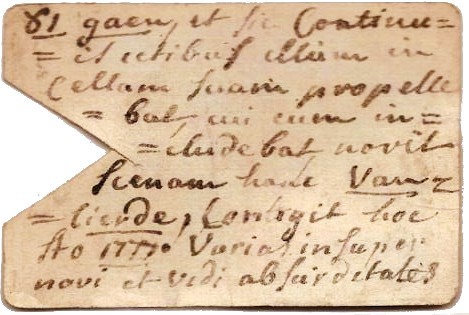

Left: reverse of 17th century French playing card used for a secondary purpose, with handwritten latin text... see more →

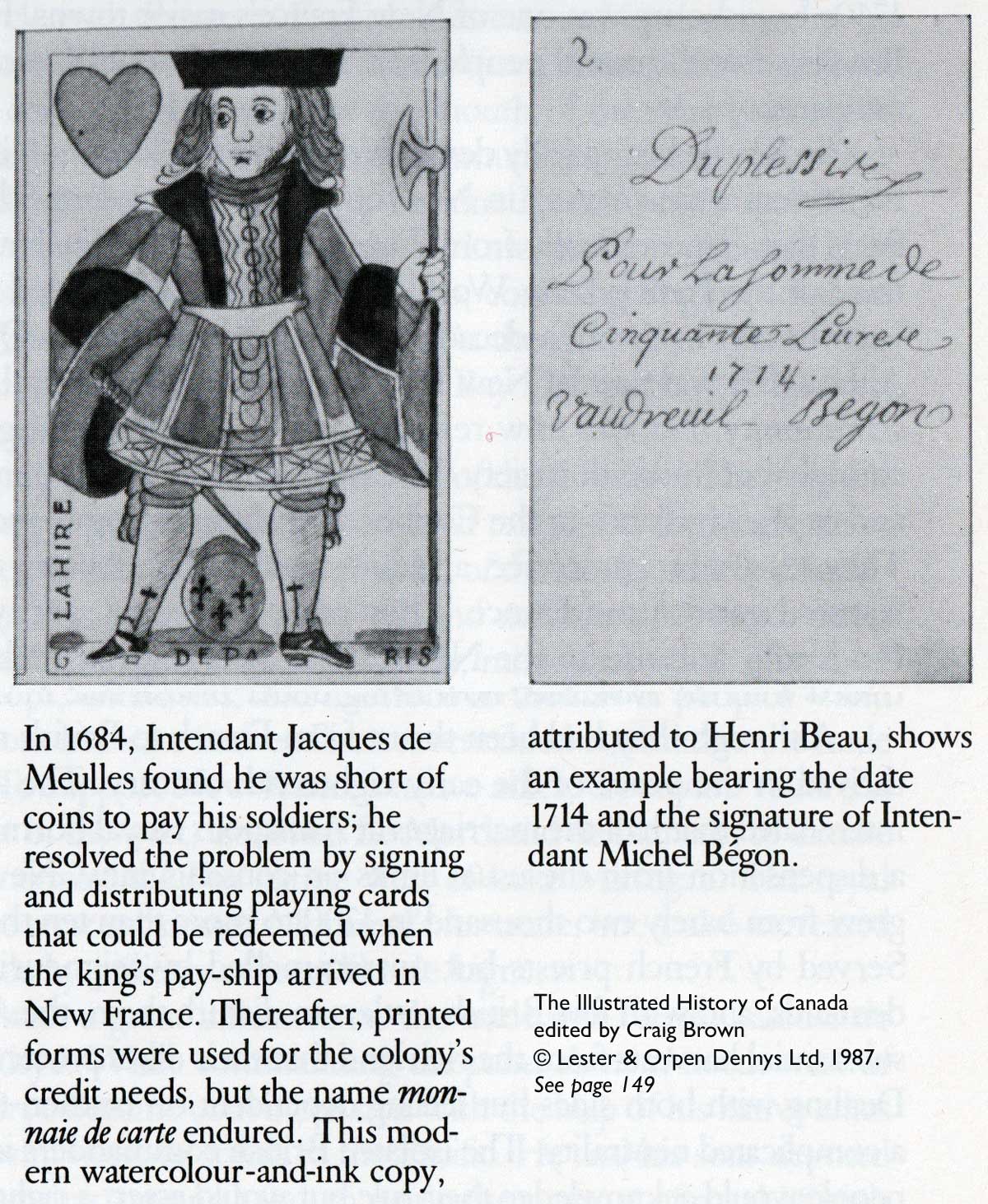

Above: from The Illustrated History of Canada edited by Craig Brown, © Lester & Orpen Dennys Ltd, 1987, page 149.

When the French in Canada were short of gold coins, they used the backs of playing cards as emergency money. Even such things as the tallying of compulsory labour were marked on playing cards. Some card backs have been found containing miniature oil paintings, or hand-drawn musical notes in some cases amounting to several vocal parts divided between several cards.

In the eighteenth century Voltaire, having unsuccessfully called on an absent friend, ‘sur une carte à jouer très sale’ wrote crossly: ‘M. de Voltaire est venu quatre fois’. Because playing cards could be conveniently carried upon the person, and did not crumple like ordinary notepaper, they were found to be handy for jotting down messages, a necessary improvement on the garbled verbal messages of illiterate eighteenth century servants.

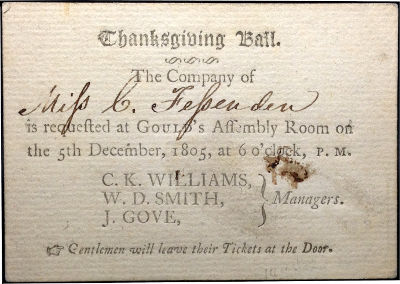

In 1749 a playing card was used as an invitation to a ball, and in 1765 playing cards were used as admission cards to the classes at the University of Pennsylvania.

According to Gejus van Diggele, secondary use is “a single playing card (or a few cards) that were produced to play games have been used for other purposes. These cards may be cut, trimmed, torn, folded, pinned, glued or pasted. On one or both sides there might be additional manuscript or printed text, drawings, paintings, doodles, musical notations or any other alteration of the original card.”

Six of Hearts: “Grace’s Card”. Baron Grace of Courtstown, in 1689, raised a regiment of foot and troop of horse for James II, at his own expense. When fighting for the King, he rejected an ultimatum from the enemy written on the Six of Hearts.

Ace of Clubs: It was on this card that Oliver Goldsmith inscribed an IOU to Sir Joshua Reynolds, intimating at the same time that this particular suitmark resembled nothing so much as the sign of a pawnbroker.

Above: four examples of playing cards where the backs have been repurposed. Images courtesy John Sings.

The link between the history of visiting cards and the secondary use of playing cards was exploited by Thomas de la Rue (see below). Other secondary uses of playing cards include bookmarks, stiffening material, transformation cards, and of course, a vehicle for fortune-telling, conjuring, taxation, education or political satire as well as advertising. (See another example here). During the 20th century advertising moved over from the backs of cards to the fronts so that we often find a King, Queen or Jack offering a drink or a cigarette →.

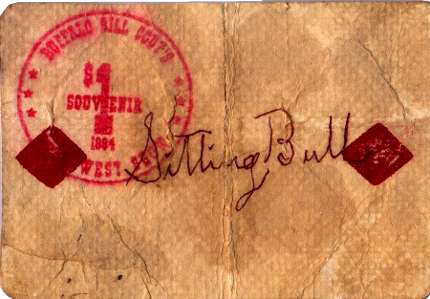

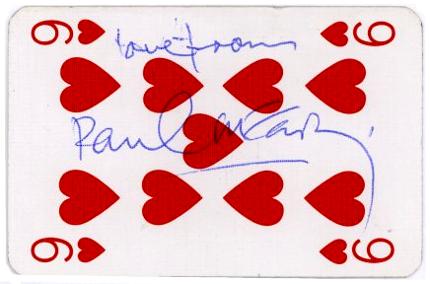

Above: two examples of playing cards used for autographs. Cases have been reported of fake "Sitting Bull" autographed playing cards.

The Invention of the Visiting Card

One of Thomas de la Rue's successful innovations to his playing card manufacturing enterprise was visiting cards. Thomas reduced the size of the cards, thereby rendering them more portable. He also used his enamelled playing-card paper which bent less easily than the flimsier, pre-De la Rue cards. Apart from inventing the modern English playing card Thomas could also be called ‘the father of the English visiting card’, or as Chambers’ called it, ‘the enamelled calling-card’.

By Simon Wintle

Member since February 01, 1996

I am the founder of The World of Playing Cards (est. 1996), a website dedicated to the history, artistry and cultural significance of playing cards and tarot. Over the years I have researched various areas of the subject, acquired and traded collections and contributed as a committee member of the IPCS and graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal. Having lived in Chile, England, Wales, and now Spain, these experiences have shaped my work and passion for playing cards. Amongst my achievements is producing a limited-edition replica of a 17th-century English pack using woodblocks and stencils—a labour of love. Today, the World of Playing Cards is a global collaborative project, with my son Adam serving as the technical driving force behind its development. His innovative efforts have helped shape the site into the thriving hub it is today. You are warmly invited to become a contributor and share your enthusiasm.

Related Articles

Copechat Paramount Sorting System

Preserving the past: a specimen deck showcasing edge-notched cards and their ingenious sorting syste...

Jeu Révolutionnaire

Court cards and aces from a French Revolutionary pack by Pinaut, Paris, c.1794.

French Revolutionary cards by Pinaut

Seven cards from a French Revolutionary pack by Pinaut featuring characters from classical antiquity...

Love Tests

Vintage novelty “Love Test” cards of a slightly saucy nature but all in good fun!

Victorian grocer’s scale plate

Large flat plate decorated with highly coloured English cards and royal arms.

76: Transitions: Hunt & Sons

Styles change and technology develops. This means that it's possible to see transition periods in th...

Rouen Pattern - Portrait Rouennais

An attractive XV century French-suited design from Rouen became the standard English & Anglo-America...

English Pattern by B.P. Grimaud

Standard English pattern published by B.P. Grimaud with engraving by F. Simon, c.1880.

Printing Presses

Antique printing presses from the Turnhout Playing Card Museum collection.

Ganjifa - Playing Cards from India

Indian playing cards, known as Ganjifa, feature intricate designs with twelve suits and are traditio...

Classification of Numeral Card Designs in French-suited packs

The classification of numeral cards in French-suited packs, covering various pip designs in over 400...

The Henry Hart Puzzle

Explore the intricate history and unique design variations of Henry Hart's playing cards, tracing th...

Sevilla 1647 reproduction

Facsimile of Spanish-suited pack produced in Sevilla, Spain, 1647.

Why our playing-cards look the way they do

Analysis of early playing card designs: origins, suit differences, standardization, technological ad...

Introduction to Collecting Themes

Playing cards can be broadly categorised into standard and non-standard designs, with collectors app...

Le Monde Primitif Tarot

Facsimile edition produced by Morena Poltronieri & Ernesto Fazioli of Museo Internazionale dei Taroc...

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 28 days