Manufacture of Playing Cards

Traditionally cardmakers worked in guilds with long apprenticeships under master craftsmen.

Traditionally cardmakers worked in guilds with long apprenticeships under master craftsmen. Arts and crafts guilds protected members' interests, orthodox methods and materials, and membership was not granted to foreigners or untrained artisans. Subscriptions needed to be paid for all the master’s helpers or employees, which would have been men as well as women. Cardmakers often worked within family dynasties with valuable skills passed down the generations. This system was gradually superseded by industrialisation as new machinery was introduced to replace manual skills. Steam power could be operated continuouly, enabling larger outputs and more profit, but less craftsmanship. This in turn might attract investment from shareholders so that more machinery could be installed. At the same time factory working conditions often deteriorated. Any surviving artisan manufacturers were obliged to lower their prices and to compromise on quality, and many ultimately went under.

The Dawning

In 1380 a certain Roderic de Borges of Perpignan was described as "pintor y naipero" and is the earliest named card-maker. In 1392 Jacquemin Grigonneur was paid 56 "sols Parisis" for three packs of gilded cards, painted with divers colours and several devices, and in 1401 the inventory of Barcelona merchant Miguel Ca-Pila includes a pack of large cards, painted and gilded [see more early references]. None of these early cards have survived, but we do have some surviving speciments from the early 1400s.

In the case of some early XV century luxury hand-painted decks (Stuttgarter Kartenspiel, c.1430) the cards are made from pasteboard consisting of up to six sheets of paper glued together, over which, on the front side, a layer of gesso was applied. Outlines of the designs were scratched into the surface, while some details were drawn in with pen and ink. The entire surface was gilded and the designs were then painted over the gold using a variety of colours and metal applications. The backs are painted a plain colour.

Above: illustration from “All the Bubbles”, c.1720 more →

The Ambraser Hofjagdspiel (The Ambras Court Hunting pack, c.1445) cards are executed in water colours and paints over black ink drawings on paper. Several layers of paper have been glued together to give the cards the necessary thickness. As was often the practice with early cards, the back paper has been cut slightly larger allowing the edges to fold over to the front, forming a border around the fronts of the cards (sometimes this border obscures part of the drawings). This artisan method of card production is more time-consuming than normal two or three-ply cards, but the resulting cards are very sturdy. It was used extensively by early Iberian cardmakers (Spain & Portugal) as well as Italian.

Around 1440 Decembrio, the official biographer of Filippo Maria Visconti, third duke of Milan, wrote that the duke enjoyed playing at a game that used painted figures. Decembrio also wrote that duke Filippo paid 1500 gold pieces to Marziano da Tortona for a pack of cards decorated with images of gods, emblematic animals and figures of birds.

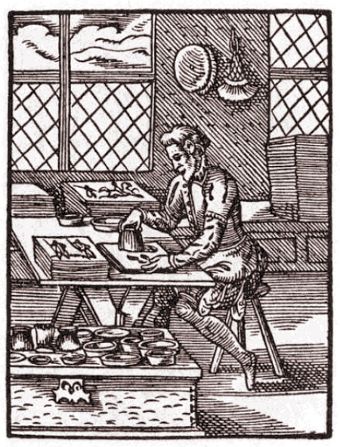

These early cardmakers were artisans, working in craft workshops, often within the guild system, producing cards for wealthier patrons. Alongside these a more rudimentary type of artefact was printed from woodcuts which led to the rapid popularity of card playing and gambling amongst the ordinary population. This soon caught the attention of the secular and church authorities, so that various bans and prohibitions were issued. The reasons given were that card playing led to brawls and irreligious behaviour, as well as financial loss due to cheating or scams►

Printing from engravings was also practised and this produced a finer quality of playing card. Over the next 200-300 years manual or artisanal playing card manufacture spread throughout Europe, and was exported from there further afield.

Extract from the first edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, volume 2 published in 1771.

Cards, among gamesters, little pieces of fine thin pasteboard of an oblong figure, of several sizes, but most commonly in England three inches and an half long, and two and an half broad, on which are painted several points and figures.

The moulds and blocks for making cards, are exactly like those that were used for the first books: they lay a sheet of wet or moist paper on the block, which is first lightly done over with a sort of ink made with lamp-black diluted in water, and mixed with some starch to give it a body. They afterwards rub it off with a round list. The court-cards are coloured by means of several stencils. These consist of papers cut through with a pen-knife, and in these apertures they apply severally the various colours, as red, black, &c. These stencils are painted with oil-colours, that the brushes may not wear them out; and when the pattern is laid on the paste-board, they slightly pass over it a brush full of colour, which, leaving it within the openings, forms the face or figure of the card.

Cards, upon sufficient security, may be exported without payment of the stamp-duty; but for every pack sold without the label of the stamp-office, in England, there is a penalty of £10. [Courtesy Matt Probert].

Industrial Manufacture of Playing Cards in 1825 ~ Article published in American Mechanics’ Magazine, September 17, 1825 *

The mode of manufacturing these common articles presents several curious circumstances: the whole process is included in five points.

- The paper of which the cards are made.

- The mode of forming the cards themselves.

- The printing and illumination of the figures.

- The mode of smoothing the cards.

- The manner of cutting them.

The paper is of three kinds: - a brown hand, which forms the centre of the card. This paper is thin, and two sheets are usually glued together to form the basis of the card. The opaqueness it imparts, and the facility with which it takes paste, are the reasons for using this paper; it is covered on one side with cardmakers' paper, and on the other by pot paper.

The cardmakers' paper, which is used for the back, must be very white; without the slightest speck, lest the card should be known by its back; for the same reason it must have no frame mark, nor the maker's name.

The pot paper is used for the printed face; it must be very white, and be slightly pasted to the belly paper, as it is termed. [...] None of these papers must be folded, for it would be impossible to get rid of the mark made by the fold.

Compare this description with that published in 1854 in Tomlinson's Cyclopedia of Useful Arts →

The pasting these papers into cards requires considerable address. The sheets of these papers are first placed in three separate piles before the cardmakers; and after the first of white, two sheets off each pile are taken in succession and placed in a pile on his left hand, the pile being finished by a single sheet of the same as that at bottom; by which means a pile is formed in which the papers required for each card are found in their proper places, but so that the cards are alternately lying on their back and their face. After this pasting is begun, and is rendered easy to the cardmaker by the single observation that the white paper is not to be spread with the paste unless a sheet of brown is to follow.

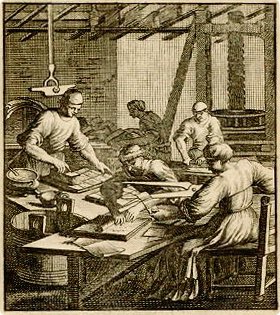

Above: the freshly pasted card is pressed. The press itself was probably inspired by wine presses in the late 14th century.

When the pasting is finished, the heap is covered with a sheet of paper, and placed under a press, which at first is but lightly screwed; but the pressure is increased every quarter of an hour, until the screw refuses to go any farther. The heap then being taken from the press, the edges are washed with a very soft brush pipped in water, to dissolve the paste that may have been squeezed out by the action of the press. The cards are then pasted together in pairs by the edges, with their backs turned to each other, for fear they should get spotted in printing or colouring.

The printing of French playing cards is usually from wooden blocks; they belong, indeed, to the cardmakers, but they are deposited in the government office, and the printing is performed there, on the government pot paper. The figured cards are always printed from two blocks; one containing two sets of the four kings and four queens, along with two knaves of clubs, and as many of spades. The second block prints ten knaves of hearts, and as many of diamonds. This arrangement arises from the circumstance that the figures on the first of these blocks are coloured with five colours, red, yellow, blue, gray and black; while the figures of the second block have no black in them. [...] Of course they print five impressions of the king block to each single one of the red knave block; and this gives the court cards for ten packs. The plain cards have a block for each suit, each containing the cards for two packs.

The yellow colour used is made from Turkey berries, with about an eighth of alum. The red of vermilion ground with gum water. The black is made of lamp black, mixed with glue, and left for five or six months before it is used, and frequently stirred. The blue of indigo mixed with size. The gray is merely a dilute blue.

The colours are applied by means of stencils, made of paper painted on both sides with several coats of oil paints. The king block requires five stencils, that being the number of its colours; the red knave block four, for the same reason. The blocks for the plain cards, as each suit is printed separately, require, of course, one stencil each.

The stencils for the figured cards are made by cutting out, with a sharp pointed knife, the space in which each separate colour is to be laid on; but those for the plain cards are cut out with a punch.

Compare this description of the Art of Stencilling with that published in 1854 in Tomlinson's Cyclopedia of Useful Arts →

The stencil for any colour being placed on the sheet of cards so as to answer correctly to the print, a quantity of colour is taken up with a soft brush, and spread thin on a board; another brush, with short, close and hard bristles is first rubbed on the newly coloured board, and then on the stencil; the brush drives the colour through the holes cut in it, and this illumines the card. The stencil being taken off, the sheet of cards is placed in a pile of one side of the illuminer; and when the pile is illumined on one face with the colour in use, it is illumined on the other face, so that the sheet of cards first coloured on one side becomes the last that is coloured on the other. The other colours are then laid on with their respective stencils.

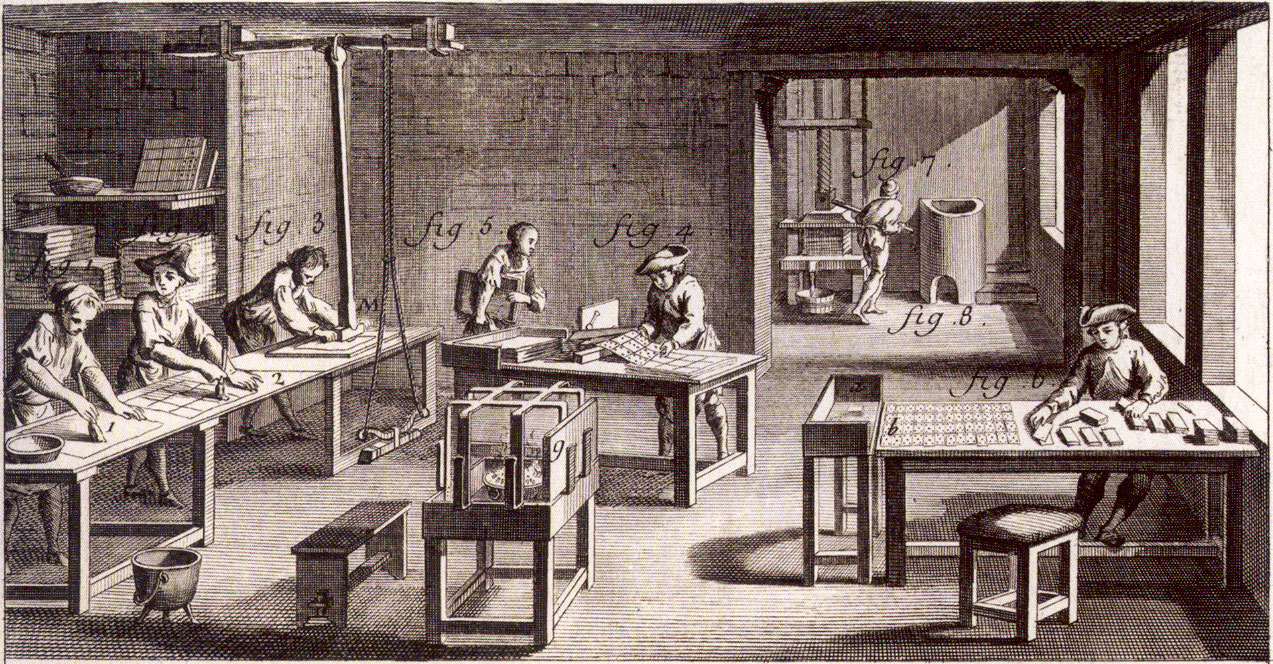

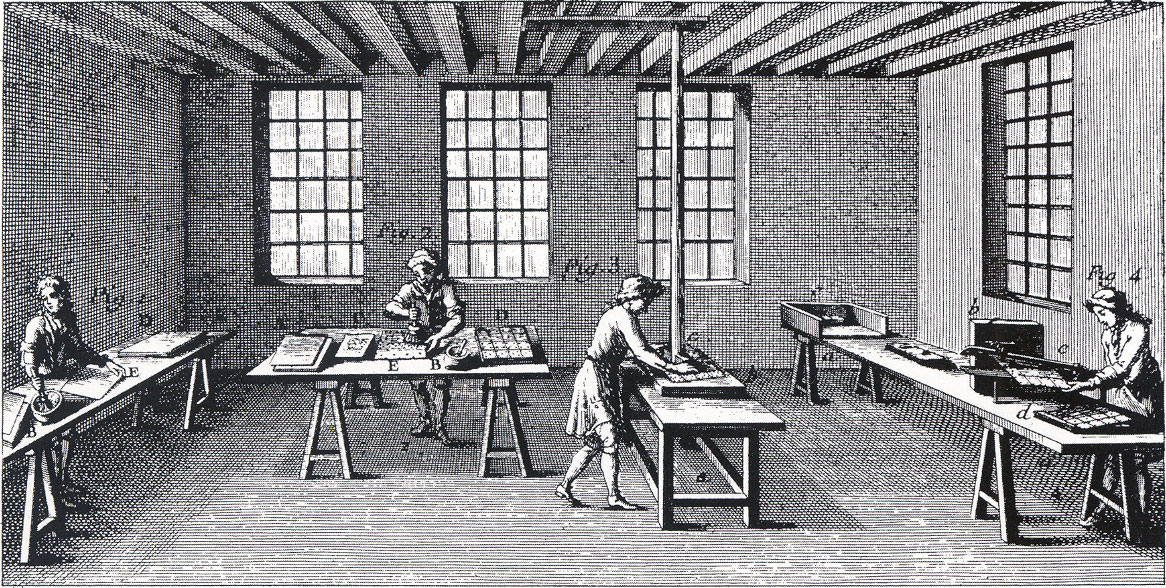

Above: the production of playing cards in 1760, from the Encyclopédie des Arts et Métiers of Duhamel de Monceau.

When the sheets of cards are illumined, or dressed as it is termed, they are separated, and each sheet is heated by itself on a square stove with a flat top; one sheet being placed on each side, and one on top; they heat very quickly, and are turned, yet so that the back of the card may be heated the most.

As soon as the colours are perfectly dry, and the sheet of cards of a proper heat, they are soaped, which is performed with a rubber made of old hats sewed together. This rubber is about three inches thick and the same size as the sheet of cards; this rubber is passed over a cake of dry soap and then over the warm sheet, first on the painted side, and then on the back.

After this the sheets of cards are polished, while hot, with a stone; the back is polished with more force, and with a more convex stone rubber than the painted side. The card sheets are then put again under the press for some time, to make them perfectly flat.

The sheets being now finished, there remains only the cutting of them into single cards. This is done on a flat strong plank, placed upright on its side, and having a raised border on the two ends. Parallel to one of these sides, at the exact distance of the length of a card, a knife edge is screwed down; and by means of a screw another knife edge is capable of being brought down in contact with it. At the other end of the table a similar knife edge is placed, parallel to the raised edge and at the exact distance of the breadth of a card.

The workman then taking a sheet of cards, with the illumined side uppermost, first cuts off the rough edge by causing the knife edge to follow the printed border: he then pushes the sheet home to the raised border and repeats the cut; proceeding in this manner the sheet is cut into four strips, each of which is then divided across into five equal parts, or single cards.

The cards thus cut are then sorted and examined: the speckled cards separated to be sold by the pound, and the perfect cards made up into packs.

This mode of making and colouring common cards may be used for manufacturing cheap illumined cards, for certain branches of education.

* The above description was published in: Hargrave, Catherine Perry: A History of Playing Cards and a Bibliography of Cards and Gaming, Dover Publications, New York, 1966, pp.297-300.

See also: Amos Whitney's Factory Inventory Chromolithography Design of Playing Cards Make your own Playing Cards Letterpress Printing Manufacture of Cardboard Rotxotxo Workshop Inventories, Barcelona The Art of Stencilling.

By Simon Wintle

Member since February 01, 1996

I am the founder of The World of Playing Cards (est. 1996), a website dedicated to the history, artistry and cultural significance of playing cards and tarot. Over the years I have researched various areas of the subject, acquired and traded collections and contributed as a committee member of the IPCS and graphics editor of The Playing-Card journal. Having lived in Chile, England, Wales, and now Spain, these experiences have shaped my work and passion for playing cards. Amongst my achievements is producing a limited-edition replica of a 17th-century English pack using woodblocks and stencils—a labour of love. Today, the World of Playing Cards is a global collaborative project, with my son Adam serving as the technical driving force behind its development. His innovative efforts have helped shape the site into the thriving hub it is today. You are warmly invited to become a contributor and share your enthusiasm.

Related Articles

Heartsette by Herbert Fitch & Co, 1893

A glimpse into a busy print and design office in late Victorian London.

Fredericks & Mae playing cards

A rainbow pack from the design team of Fredericks & Mae and Benjamin English.

Printing Presses

Antique printing presses from the Turnhout Playing Card Museum collection.

Lo Stampatore

‘Lo Stampatore’ linocut images created by Sergio Favret, published as a deck of cards by Editions So...

Lorilleux International

Promotional pack for Lorilleux International’s Lotus inks, with designs by James Hodges.

Dreveton - Provence pattern

French cardmakers Jean and François Dreveton lived in Aix-en-Provence.

Cartavi

Promotional pack for AVI paints, with 54 different colours on the backs.

Imperial Club playing cards

Large index broad size cards by AGMüller using a special red ink suitable for casinos.

Lithographic Stone

Historic lithographic stone from the Fournier playing card factory, c.1888.

H.P. Doebele

Artist-designed playing cards produced to demonstrate the quality of a printing technique.

Bon Gout No.11 with Crimean War aces

Made by Mesmaekers & Moentack of Turnhout.

Luxury Collectable Playing Cards

Luxury packs of cards have been produced since the 15th century, a trend that is very popular among ...

Geschichte des Buchgewerbes

Geschichte des Buchgewerbes illustrated by Ludwig Winkler, published by Verlag für Lehrmittel Pößnec...

Rainbow

Rainbow card game and colour mixing guide printed by Goodall & Sons for Robert Johnson, c.1920.

Master of the Playing Cards

Animal suited playing cards engraved by the Master of the Playing Cards, Germany, c.1455

Lilian Cailleaud’s Tarot Project

Lilian Caillaeud lino-cuts his version of the tarot by Nicolas Rolichon of Lyon c.1600

Most Popular

Our top articles from the past 28 days